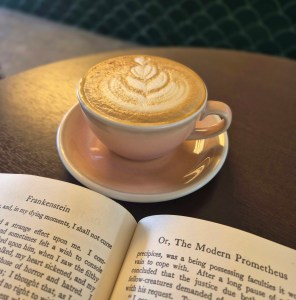

There is a vague memory of my pre-teen self poring over a Signet Classic mass-market paperback edition of Frankenstein. I don’t think I was as interested in the first sci-fi novel as much as I was in the context in which it was written.

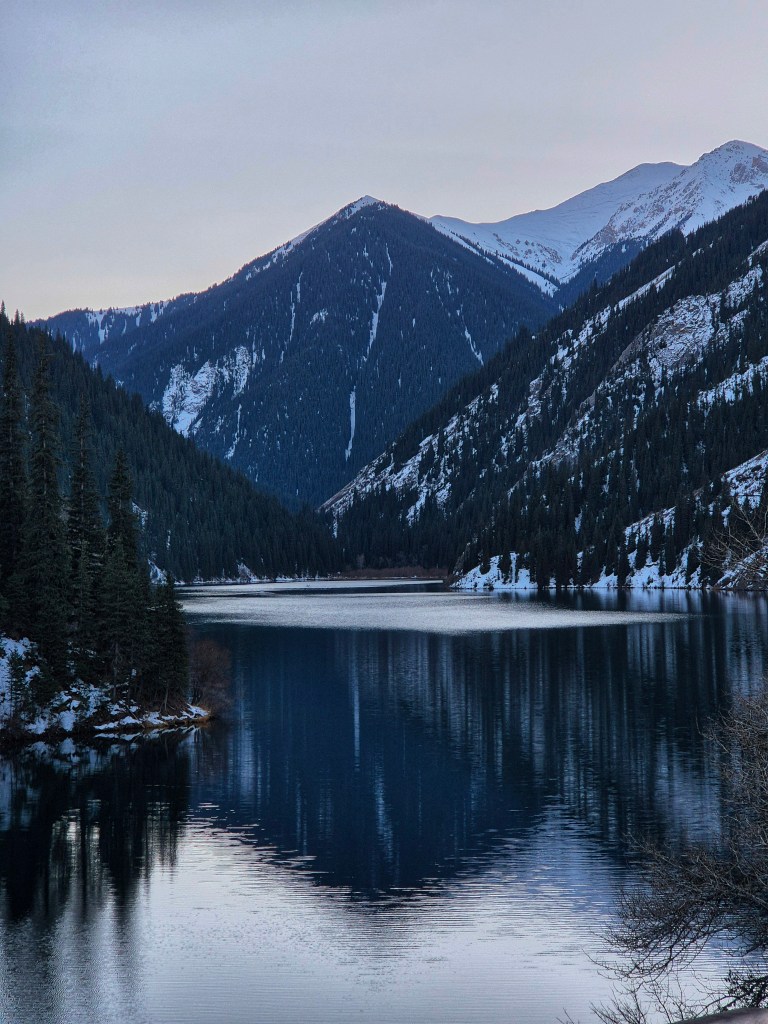

The scene in my mind’s eye mimics a Caspar David Friedrich painting: Three figures surrounded by snowcapped mountains on the shores of a lake in Switzerland, faces illuminated by warm firelight. Fire was the source of light, because though the century was already charged with scientific possibility, the world was dark then: The electric battery forged by Alessandro Volta was still nearly as young as the girl, and the light bulb had yet to be invented. The trio consisted of eighteen-year-old Mary, namesake of her mother the pioneering feminist; the poet that would become her husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley; and his best friend, Lord Byron. It was the latter who would suggest that each should come up with a story built on a supernatural theme, “As a source of amusement”.

Lord Byron penned a poem called Prometheus that year, and Percy Bysshe Shelley would author a lyrical drama called Prometheus Unbound four years later, but only Mary Shelley would complete a novel as an answer to the challenge raised on that consequential evening: Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus.

Needless to recount the story of Prometheus, but one can see how this complex character associated with creation inhabited the greatest minds of the era. Even though I failed to recognize the significance of Frankenstein’s story as a pre-teen, maybe I acknowledged the value it would have to an older self when I replaced the paperback with a hardcover edition in my late teens. Thanks to Guillermo del Toro, the hardcover ceased to gather dust and was paired with the film.

Right from the beginning, one can immediately detect the drastic difference between book and movie, and somehow, I prefer it this way. I like a filmmaker who announces, right at the onset, that he is creating something entirely different in an adaptation, rather than one who copies most of the text and be unfaithful to some. The book introduces us to noble human characters, the film with sinister ones, and this is necessary in determining the course of its diverging narratives. The book puts emphasis on how man and his ambition creates its own monsters; in the film, man is the monster.

If one wants a film that comes close to what Mary Shelley intended to say, there’s Oppenheimer, whose main character also becomes an “author of unalterable evils”. If one wants contemporary literature that reinforces her cautionary tale, there’s Benjamin Labatut’s books.

But you know what the Frankenstein film beautifully captured from the novel? My favorite part. It’s when the Creature discovers reading. I loved that artistic choice of making him read Ozymandias — a fitting piece, but also a nod to Mary Shelley’s husband, who wrote the poem. In both art forms, we get a creature who is better-read than the average man. Let that sink in, says Mary Shelley and Guillermo del Toro.

And what does Emily Bronte tell us in what seems to be another Elordi-instigated rereading? A screen adaptation of Wuthering Heights will forever be unnecessary, thank you. Sufficient unto the novel is the intensity, the complexity, and the viscerality thereof.