Not the West Bank this time, just the Left Bank. The thing about my Silk Route | Fertile Crescent reading project is that — despite being a source of enlightenment through discovering underrated but astounding literature — novels from this route in question are usually emotionally taxing.

Although I have sensed that I am drawn to writings from places of conflict for the reason that they have a sensitivity to beauty commensurate with their heightened awareness of the fragility of life; once in a while, I need a breather, and that’s when I turn to books related to other interests. In this case, not merely an interest, but a love.

But as love would have it, we oftentimes become accustomed to a beloved’s presence and we slowly take its magic for granted.

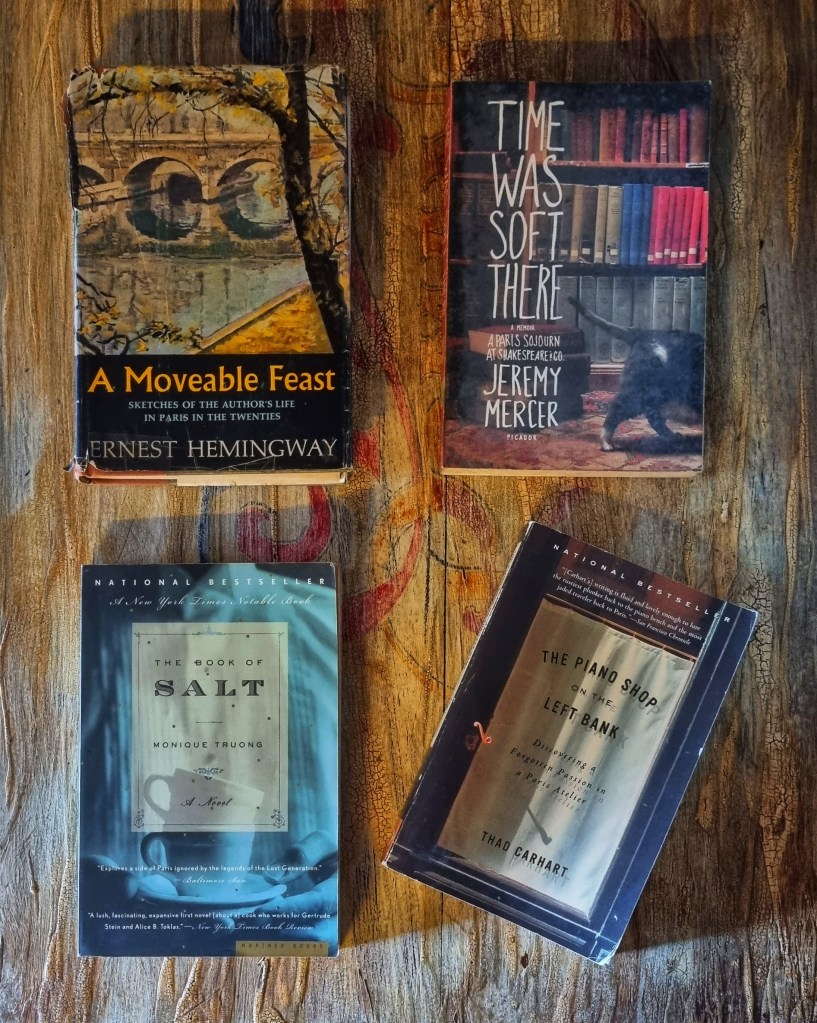

The Piano Shop on the Left Bank: Discovering a Forgotten Passion in a Paris Atelier refreshed me about the intricate workings of a piano; of how extraordinary this instrument is; of the alchemy and difficulty involved in piano-making and music-making; and how beautiful tone production relies so much on the precision of piano makers, the skill of piano technicians, and the heart and hands of a pianist. This rekindled a fire that led me straight to the piano after turning the last page.

But this book is not just about pianos and trivia from the music world. (Although, while we’re at it: Did you know that when the Eiffel Tower was built in 1889, the first thing to be hauled to the rooms at the top was a piano?) It is also about the Paris that is inaccessible to the tourist. In fact, this would make a lovely pair to Mercer’s Time Was Soft There: A Paris Sojourn at Shakespeare & Co.

Surely, these books did not intend to rival Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast or the aching poignancy of Truong’s Book of Salt, but at times, lesser-known books are beautiful for the simplicity that they lead us to find something that draws out music from within.