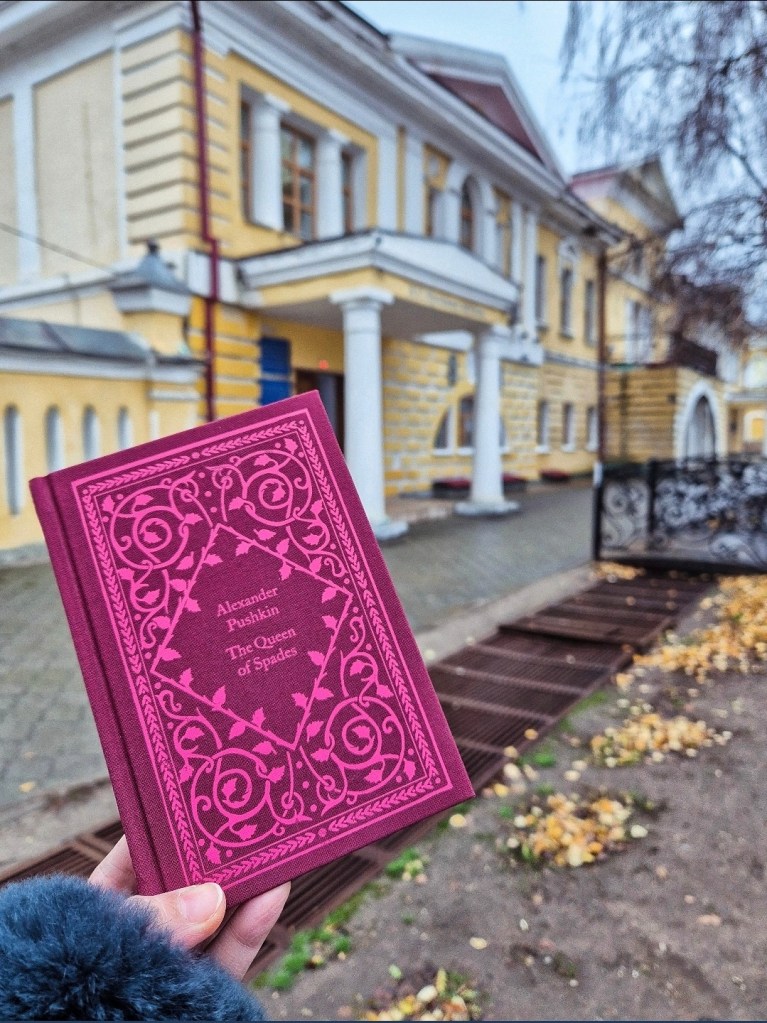

The city is now descending into winter. At 9:00 A.M., the sky is unlit, and even at noon, the sun barely makes its presence felt. But I love strolling around despite the dark and the freezing temperature and seeing the onion domes of Orthodox churches appear through the mist, adorable babushkas wrapped in headscarves who are up before everyone else, and the warm lights emanating from old windows that reveal hidden coffee shops that offer respite from the cold. The baristas do not speak English; hardly anyone does, but they have smiles that translate enough warmth to this strange, shivering girl with a book.

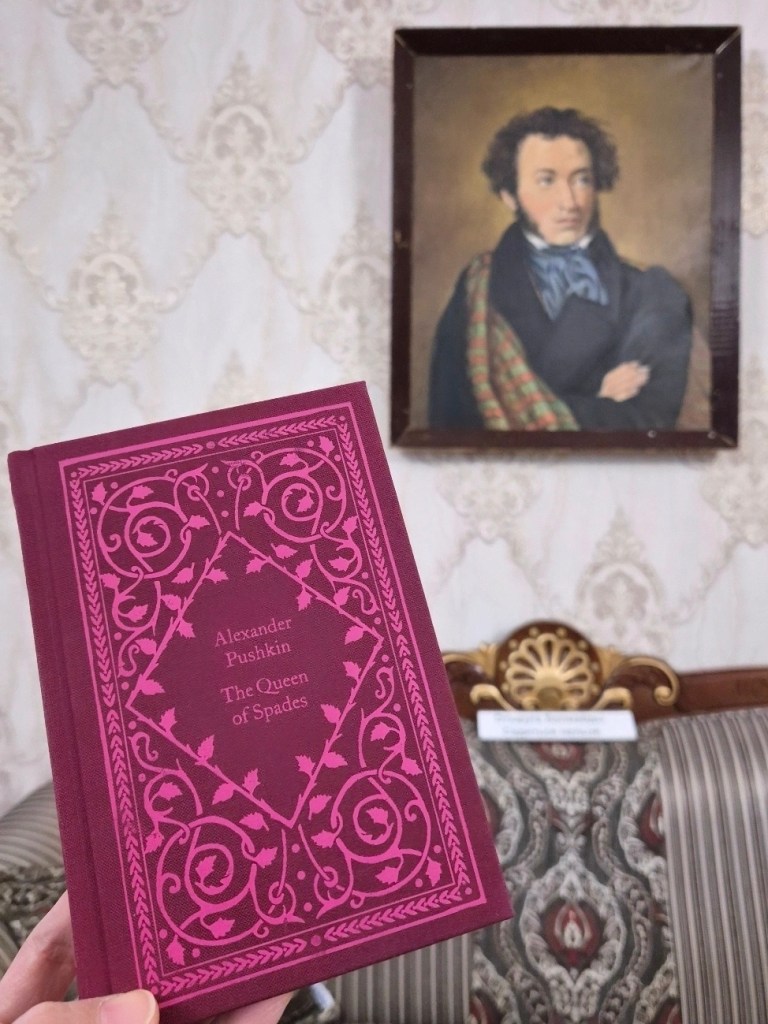

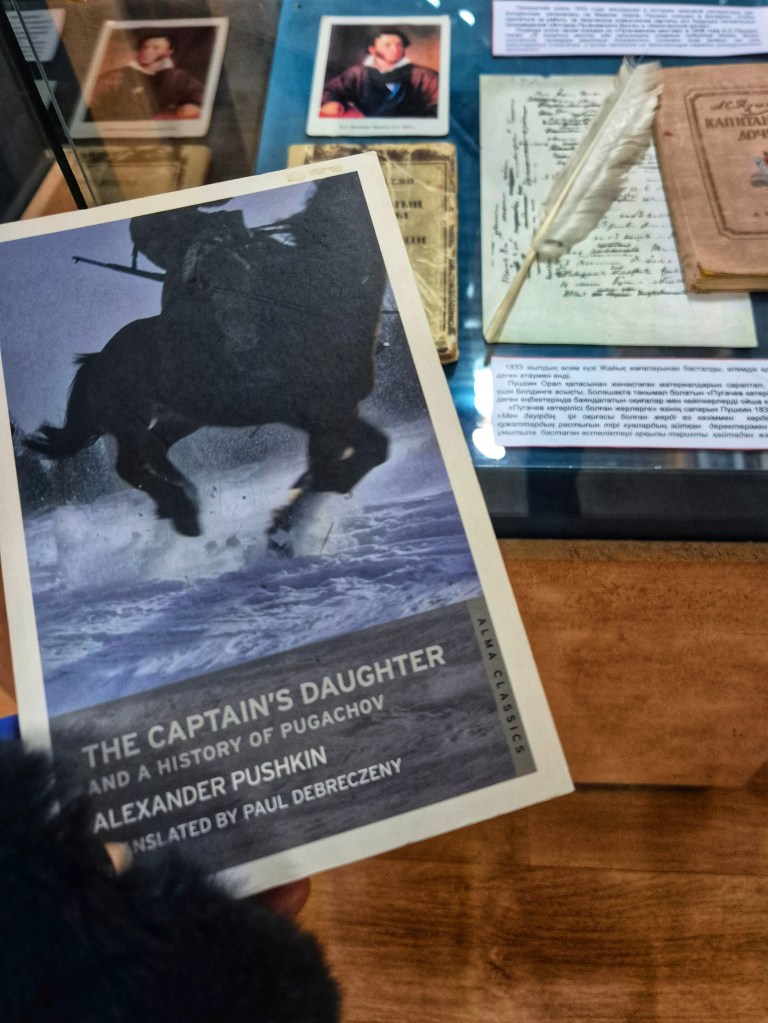

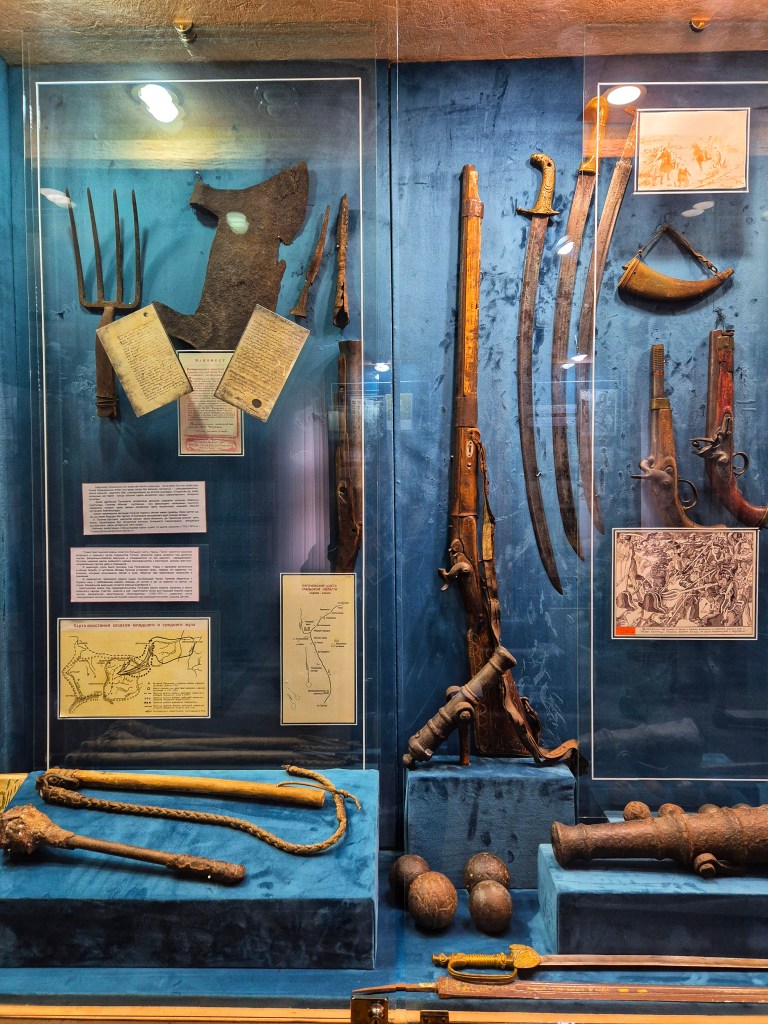

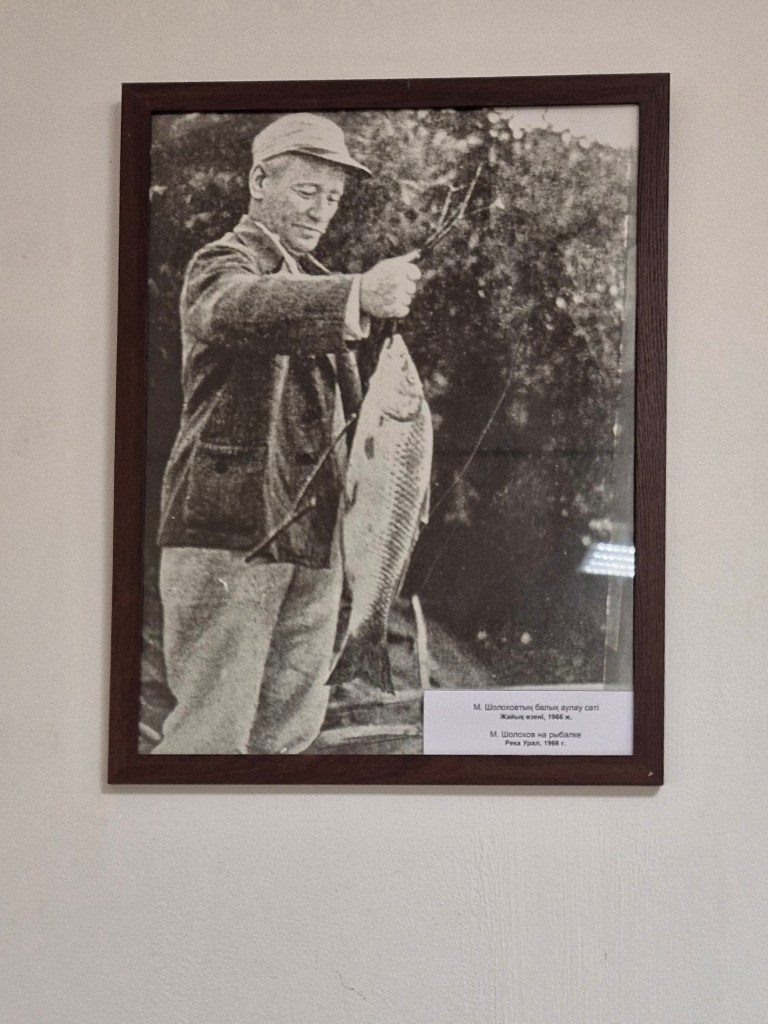

Its side streets and residential areas are pages out of a Gogol story. It is, after all, quite a literary city. It was here that the first and enduring public library in Kazakhstan was established in 1871. Pushkin, Tolstoy, Sholokhov and other literary greats have come to Uralsk and made their mark here. I booked at the Pushkin Hotel, predictably.

The distance between Almaty and Uralsk is several chapters or a few hundred pages of a Russian novel. For a different perspective: Uralsk is closer to Kiev, Moscow, Warsaw, Vienna, and Helsinki than it is to Almaty. The oldest city in what is now Kazakhstan, Uralsk was founded by Cossacks in 1584 as a border outpost of the Russian Empire.

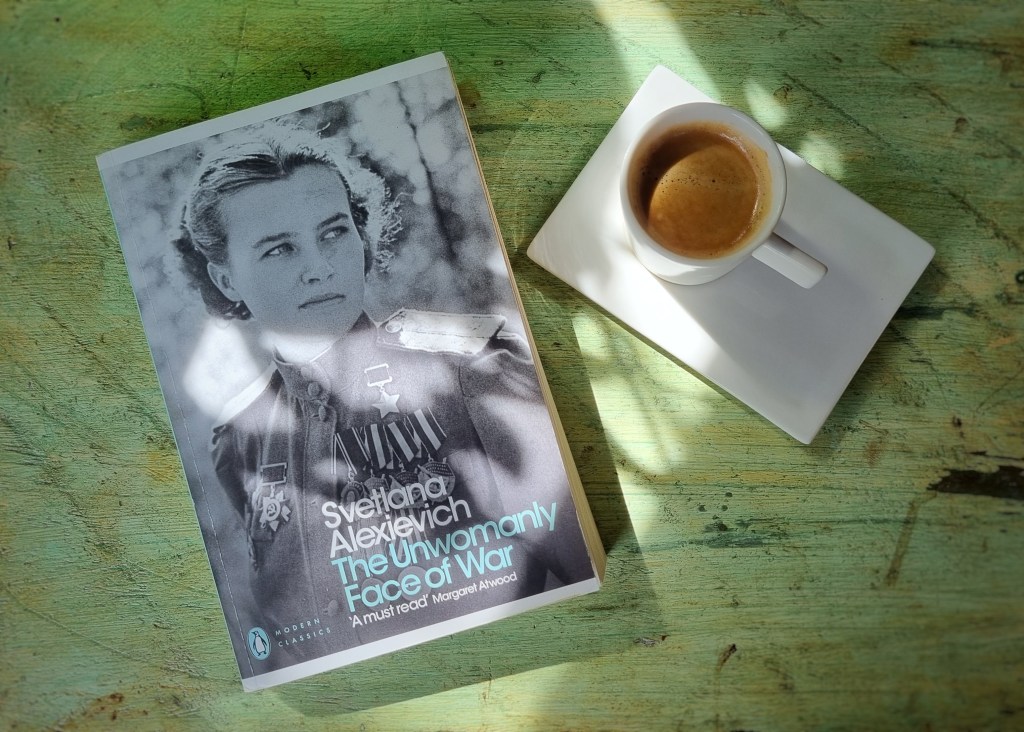

Perched on the European bank of the Ural River, it is geographically within Europe. It is where Central Asia ends, or begins, depending on where you’re coming from. But if you’re coming from a book, as I am, it is where Russian literature comes alive.