“Do not travel to Yemen due to terrorism, civil unrest, health risks, kidnapping, armed conflict, and landmines. Avoid all travel to Yemen.”

I was constantly met with these words when, during lockdown, I made itineraries for the places I hope to visit in the future. If you know me well enough, I’ll probably be one of the first people you’ll think of whenever you see photos of the architecture in the old city of Sana’a, that stone house in Wadi Dhar, and the otherworldly trees and landscape of Socotra.

The hostile travel advisories did not prevent me from coming up with an itinerary, but my rational side knows it would be safer to travel to Yemen through literature for the time being.

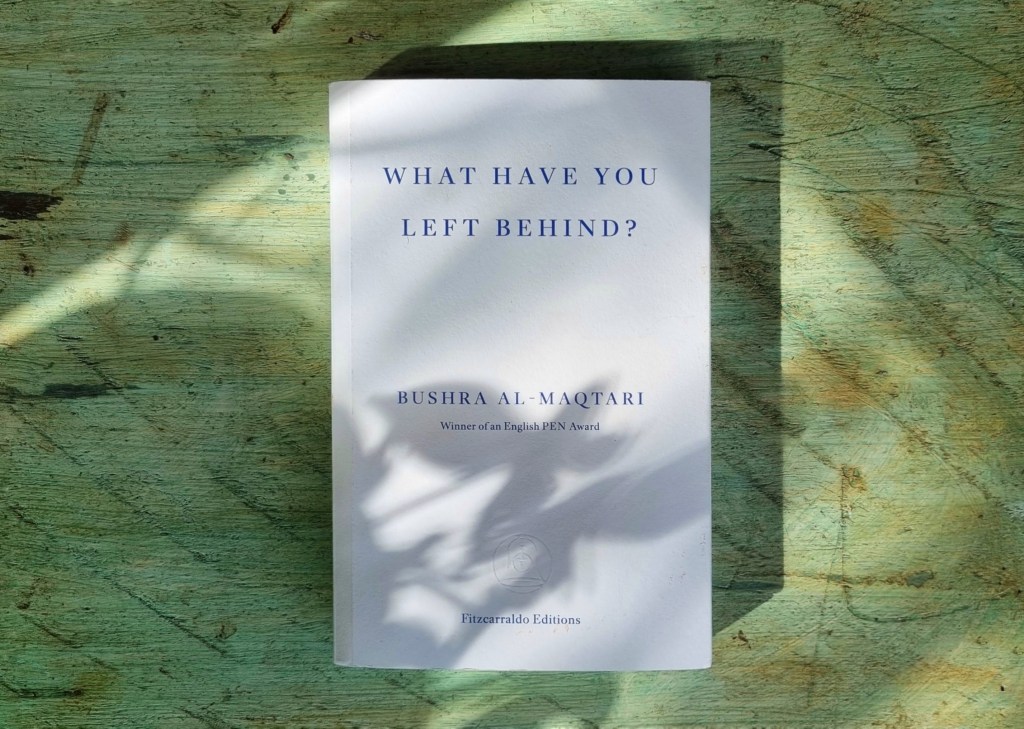

Unfortunately, authors writing about, and especially those from, Yemen are hard to come by. You can imagine my eager anticipation when Fitzcarraldo Editions announced the launch of this book!

Warning: Do not read this in public. Unless you’re okay with weeping in public.

Every page is drenched in heartache and death. It’s the kind of book that Scholastique Mukasonga would call “a paper grave”. A book to put my puny troubles into perspective.

But I think my task as reader is not to highlight how this book made me feel; it’s to sound the sirens and ask others to take time to look into what is happening in a country that hardly enters the fringes of our consciousness.

Inspired by the work of Belarusian journalist and 2015 Nobel Prize laureate in literature, Svetlana Alexievich, Bushra Al-Maqtari traveled across her own war-torn country for two years to document the lives and deaths of civilians caught in the crossfire of the civil war that erupted in 2014 and which persists up to this day. But unlike Alexievich, Al-Maqtari lived, and continues to live, through the war of which she writes.

This war has claimed hundreds of thousands of innocent lives, only to serve the greed for power of a few. The least we can do is listen, read, encourage others to do the same, and allow the power of fearless journalism and literature to achieve its goal.

Exceptionally written, it is an essential education and addition to a journalist’s shelf, or any human being’s shelf for that matter. It is a precious but painful work of journalism that makes me wonder at how difficult it must be to gather, to write, and to live these stories — especially as a woman.

The book is the result of one woman’s courageous initiative: “…to ward against forgetting, against feigning ignorance, against indifference,” to emphasize that the Yemeni people “are not voiceless, they are unheard.”

Listen.