“Sonia’s heart was a Hopper painting.” The title is blunt about Sonia and Sunny’s loneliness, but it’s this Hopper line that makes one grasp how lonely: A profound loneliness that has something to do with a vulnerable and fluctuating selfhood, an abstract loneliness that is tied to urban and modern life, an existential loneliness craving real connection that cannot be quenched by mere companionship. Lonesomeness was Edward Hopper’s leitmotif, and Kiran Desai weaves this theme into an unfolding raga… Read full entry here.

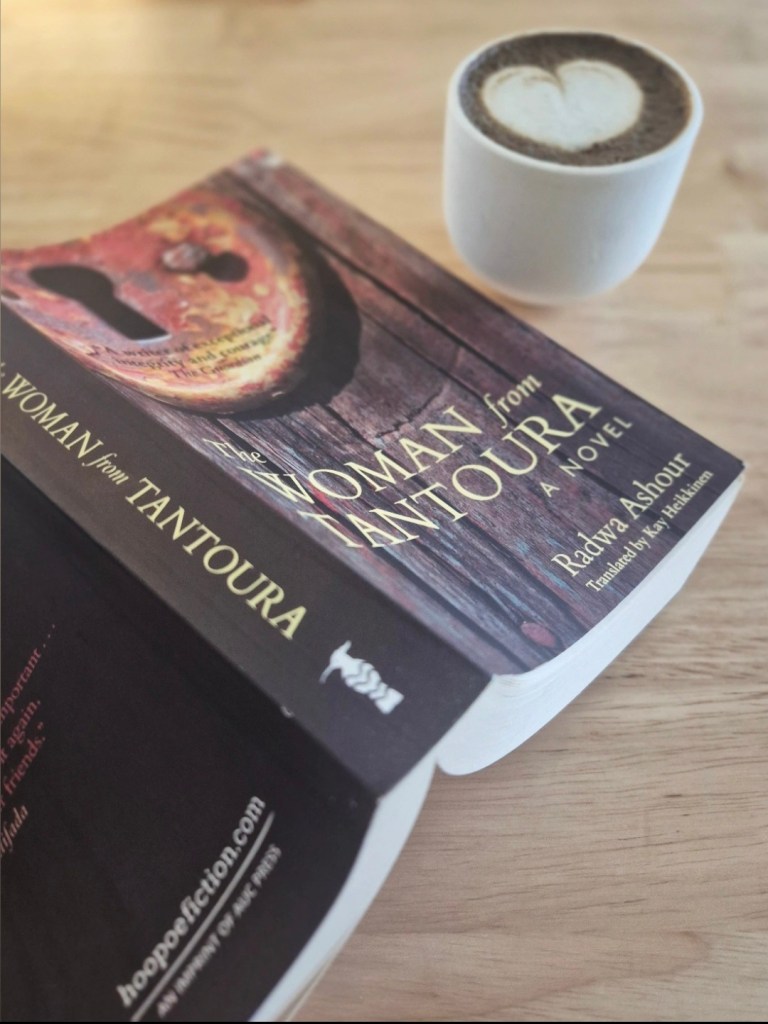

The Woman from Tantoura was my pick for #ReadPalestine week. Radwa Ashour’s best work, if you ask me. Started 2025 with Edward Said and ended it with something a bit less intellectually demanding, albeit informative and genuinely affecting. Why #ReadPalestine? Until we know enough to be able to call a spade a spade.

Brightly Shining by was my hope for a more festive read, and my first Dua Lipa recommendation. Surprisingly, all three books touch on immigrant life, and two have Filipino minor characters. But this one broke my heart.

It makes me extra grateful to have been able to squeeze in Tethered on the last day of 2025. Not because it helped me achieve my goal of reading at least one Filipino author a month, but primarily because this book is a gift. Grace is a multifaceted word, but even when I contemplate its various meanings, this book still embodies all of its definitions. Read full entry here.

That’s my December in books. The 2025 reading wrap-up will have to wait. It’s a wonder I was able to read at all with all the season’s bustle while caring for a loved one who was ill for most of the month, leaving me to (wo)man the fort. But we said goodbye to 2025 on a healthier and happier note. Gave and received bookish presents. Attended the last Ex Libris session of the year and felt revitalized. BFF paid us an impromptu visit: We attended a Rizal Day literary event and said goodbye to the old year / welcomed the new year reading quietly… and it was precious.

Wishing all my reading friends a happy new reading year!