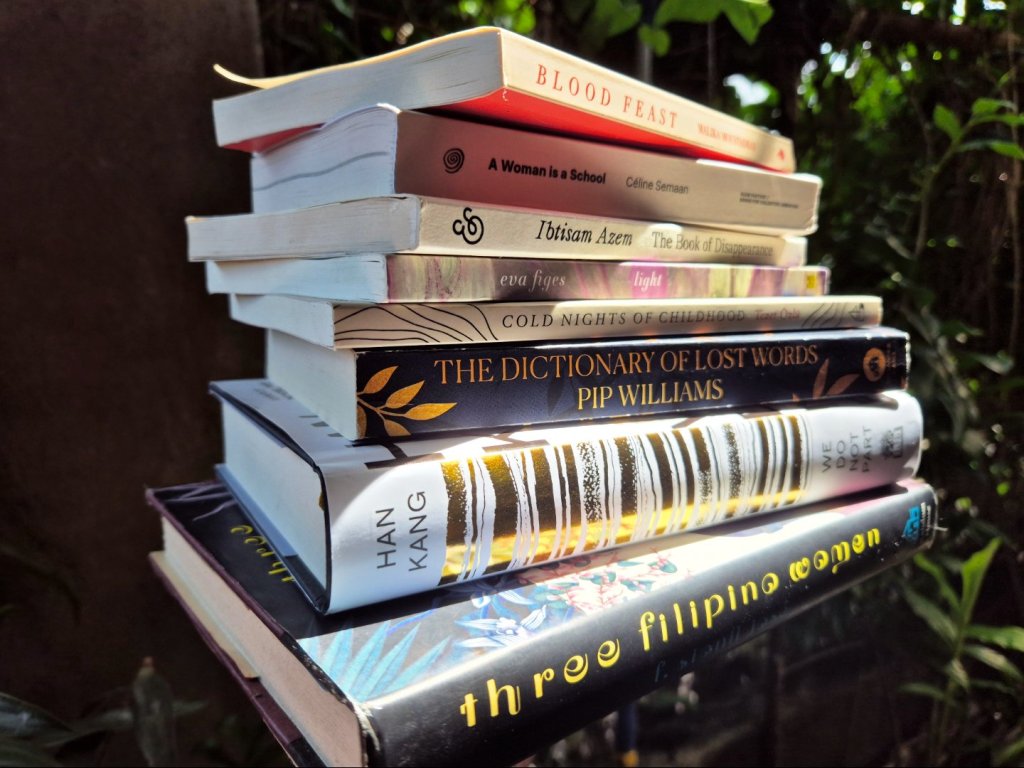

Blood Feast, Malika Moustadraf

Malika Moustadraf is Morocco’s answer to Egypt’s Nawal el Saadawi whose depictions of how women are viewed and treated are unflinching. But Malika has a distinct style that draws the reader right into a scene, into the midst and into the cracks of such a society, sometimes forcing us to look through the eyes of the scoundrels themselves. I daresay she is the more masterful fiction writer. Fiction, as we know, is just a tool to reveal the rawest of truths. Read full entry here.

A Woman is a School, Celine Semaan

Even though this one did not exceed my expectations, it has its merits. I love how she writes of art as “the ultimate act of giving.” It may be enlightening to someone younger who is reading about the effects of colonialism for the first time, but readers may find more substantial memoirs and more informative books on Lebanon and Lebanese culture, and better books that encourage attentiveness to social justice.

The Dictionary of Lost Words, Pip Williams

An exceedingly apt book for Women’s Month that would also make a splendid companion read to Simon Winchester’s The Professor and the Madman. It is this one that left my heart with a tender aching.

“Never forget that… Words are our tools of resurrection.”

The Book of Disappearance, Ibtisam Azem

In another Palestinian masterpiece, Adania Shibli’s Minor Detail, the entire book is a bullet in motion that hits you with a staggering force on the very last page. There is an abrupt and brutal finality. There is no closure in Ibtisam Azem’s The Book of Disappearance. It ends without a concluding cadence and leaves the reader suspended in an unsettling limbo. But that does not imply that this book pales in comparison. Perhaps we are given a nanoscopic glimpse of what it feels like to be Palestinian. Read full entry here.

We Do Not Part, Han Kang

“Extermination was the goal. Exterminate what? The reds.” But Jeju’s inhabitants were not all reds, and yet it was easier for the military to operate by decimating the population. For nearly fifty years after the massacre, it was a crime punishable by law for a South Korean to mention the event. A huge percentage of the thousands that perished were innocent.

“Collateral damage.” That’s what they call it. Now where have I heard that term recently? Read full entry here.

Cold Nights of Childhood, Tezer Ozlu

Bursts of beauty in the prose amidst a stream of surreal disclosures from a woman grappling with mental illness and electroshock therapy. But it is ultimately a sad and disturbing portrayal of a particular societal context and its effect on the psyche, framed affectionately by Aysegul Savas’ introduction and Maureen Freely’s translator’s note. Read full entry here.

Light: Monet at Giverny, Eva Figes

An impressionist painting in book form with the most elegant feminism I have ever read.

“I’m sitting at the restaurant reading. Some books take me to worlds far greater and more tender than real life.” This line was lifted from Tezer Ozlu. She could have been referring to this book. Amidst the cacophony of social media and political rants, my mind is thankful to have been transported and softened by such a beautiful, beautiful book!

Three Filipino Women, F. Sionil Jose

This reader’s Women’s Month has usually been reserved for reading women authors, but an exception had to be made for this. Curious as to how a man would paint a portrait of the Filipino woman, I soon realized that this is more portrait of Philippine politics than it is of the Filipino woman. It is a dismal but virtuosic depiction. Three women: A politician, a prostitute, and a student activist. Maybe parable, maybe allegory, maybe both. Beyond death, F. Sionil Jose reminds me, once again, that he was the closest thing the Filipinos had to a Nobel laureate in literature.