“No books!” I exclaimed.“How do you contrive to live here without them? …take my books away, and I should be desperate!”

(This line is found toward the end of Wuthering Heights, and for once, I agreed with something that a character from the novel had said.)

A little late in posting, but this was January — a beautiful reading month ripe for the picking — in books:

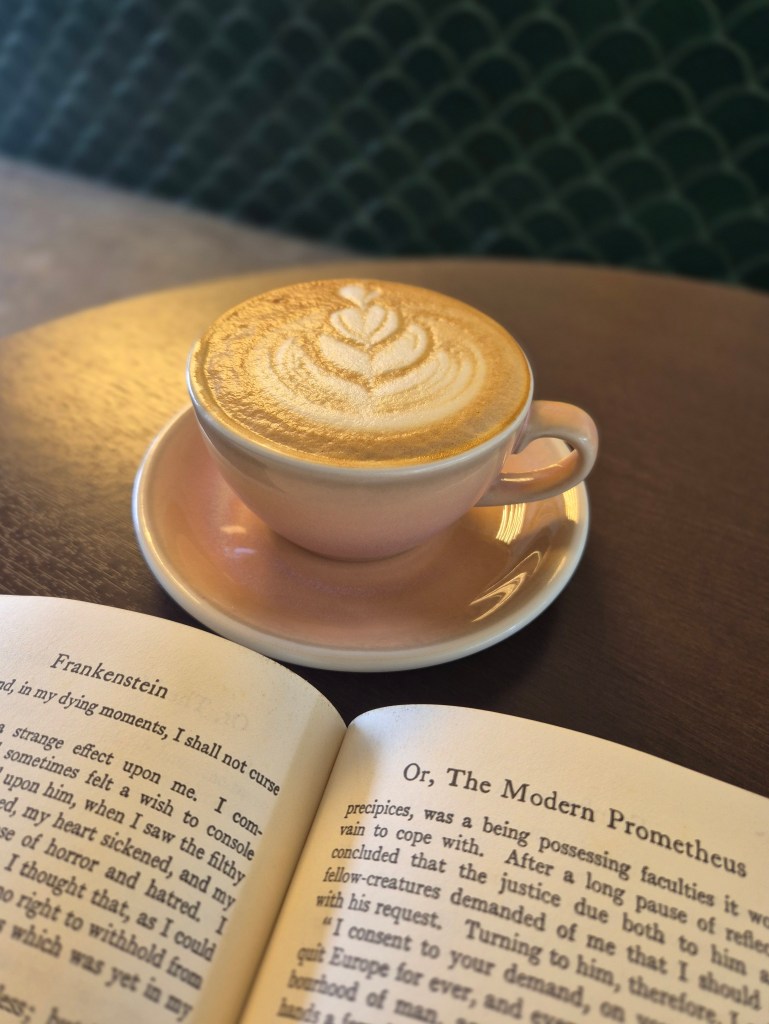

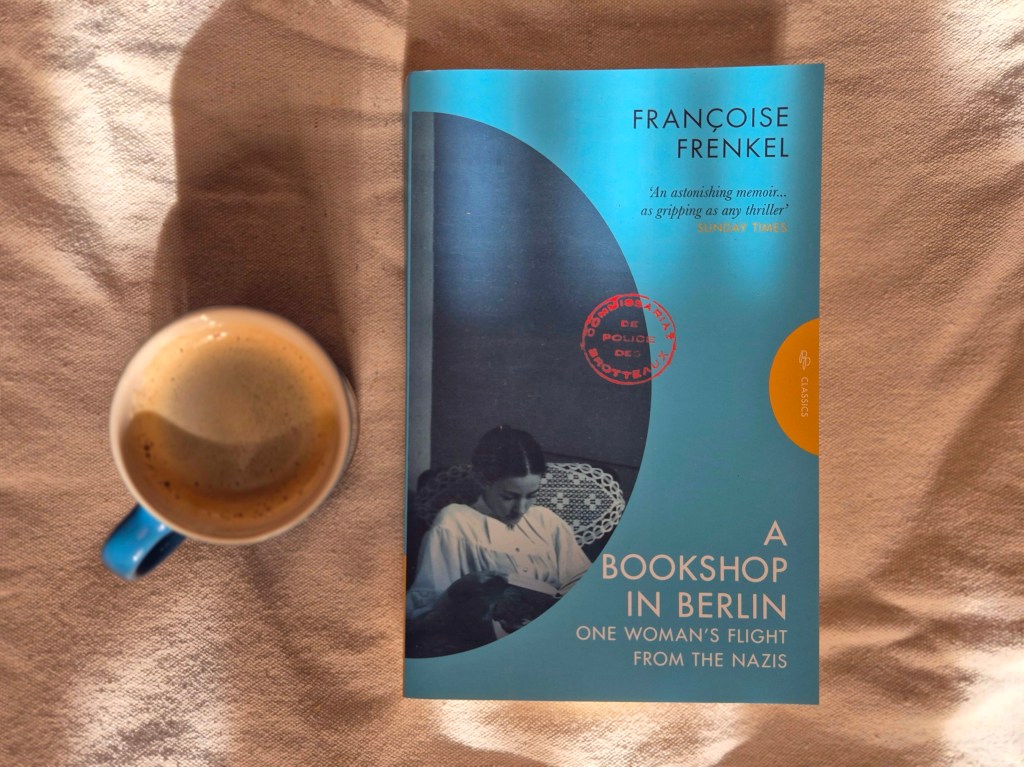

Frankenstein, of which I wrote at length in a separate post, was a wonderful way to ignite yet another year of reading, followed by the literary experience that is Wuthering Heights, which convinced me that any screen adaptation will forever be unnecessary. Sufficient unto the novel is the intensity, the complexity, and the viscerality thereof.

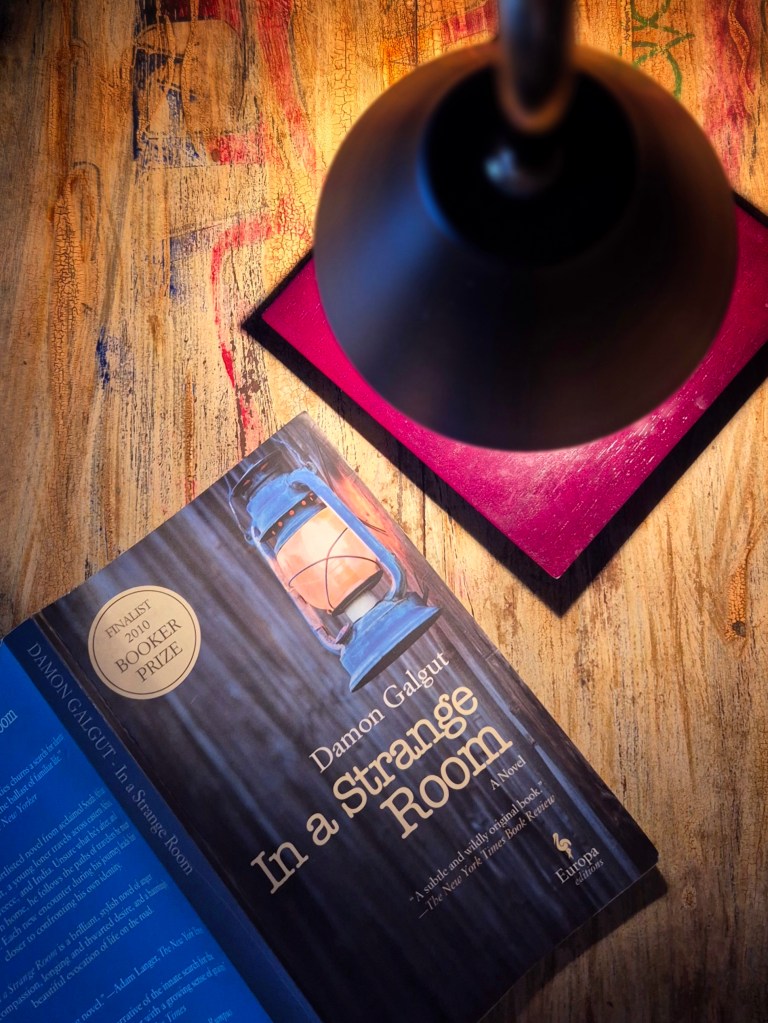

A Strange Room, given to me as a Christmas present, strangely seems to converse with Emily Brontë. “Nothing fuels revenge as grief does,” Damon Galgut says, as if writing of Heathcliff. To which Brontë replies, “Proud people breed sad sorrows for themselves.”

“Without love nothing has value, nothing can be made to matter very much.” Maybe Brontë, maybe Galgut. Guess?

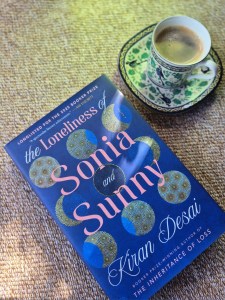

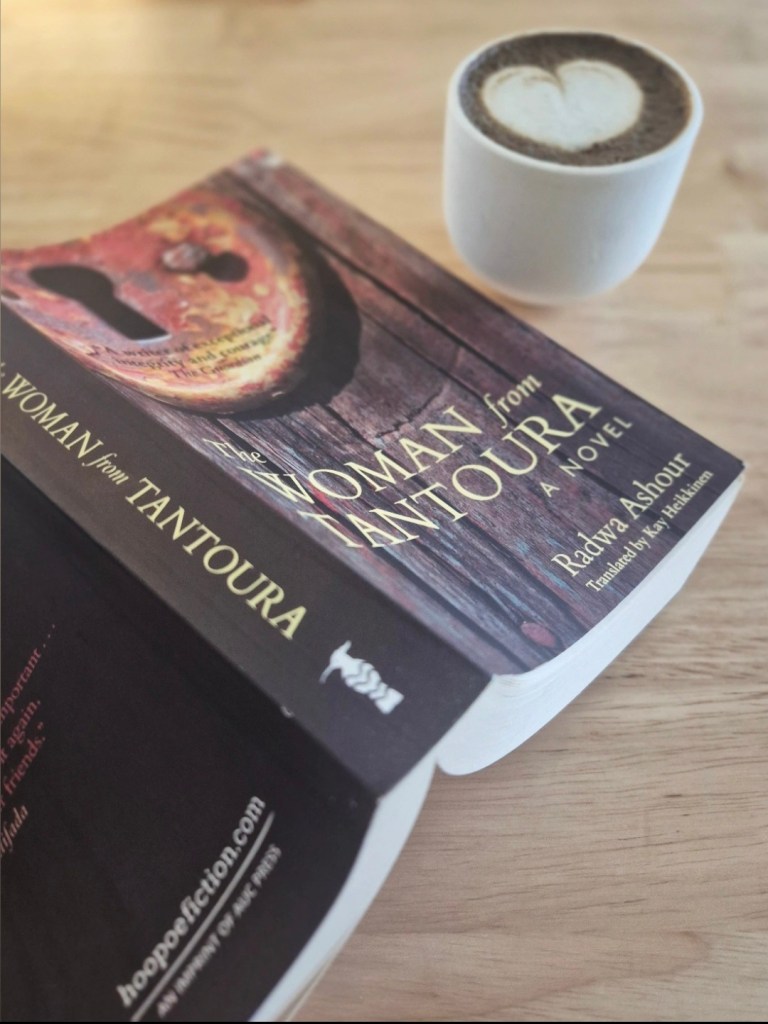

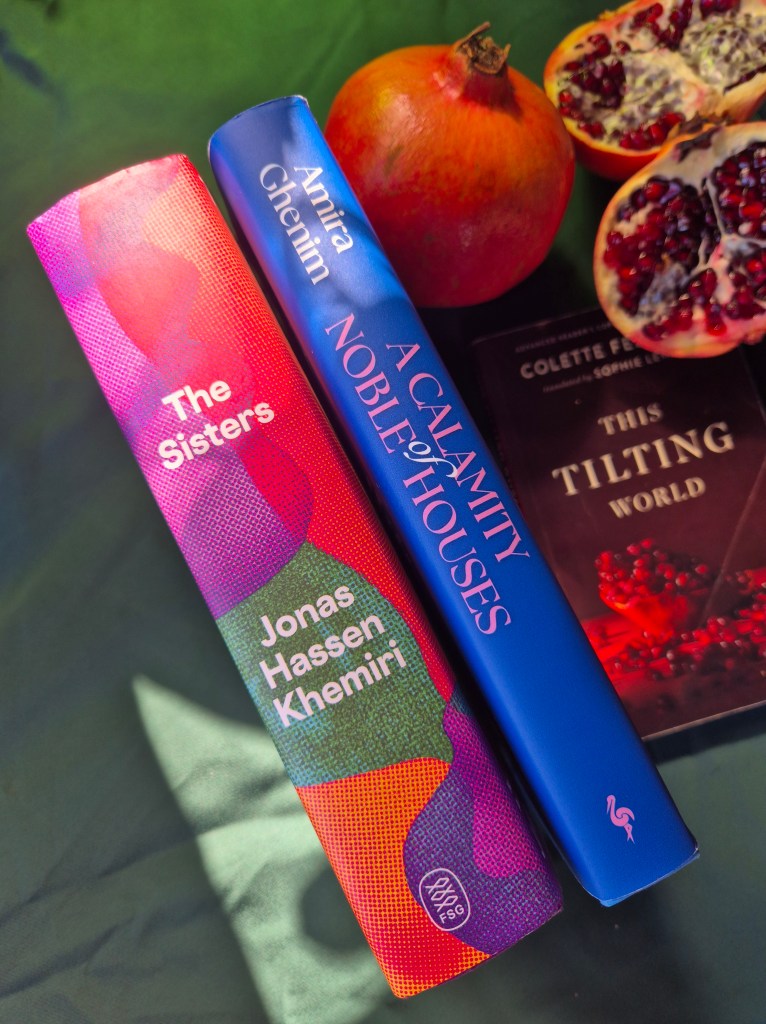

From Galgut’s South Africa to North Africa. People ask how I pick my travel destinations. It usually starts with a section of this library that’s mostly arranged by political geography. And it seems like a Tunisian section is born: A Calamity of Noble Houses, an intriguing peek into the historical and social mosaic of Tunis; The Sisters, a 656-page glimpse of the diaspora. The books decide for me.

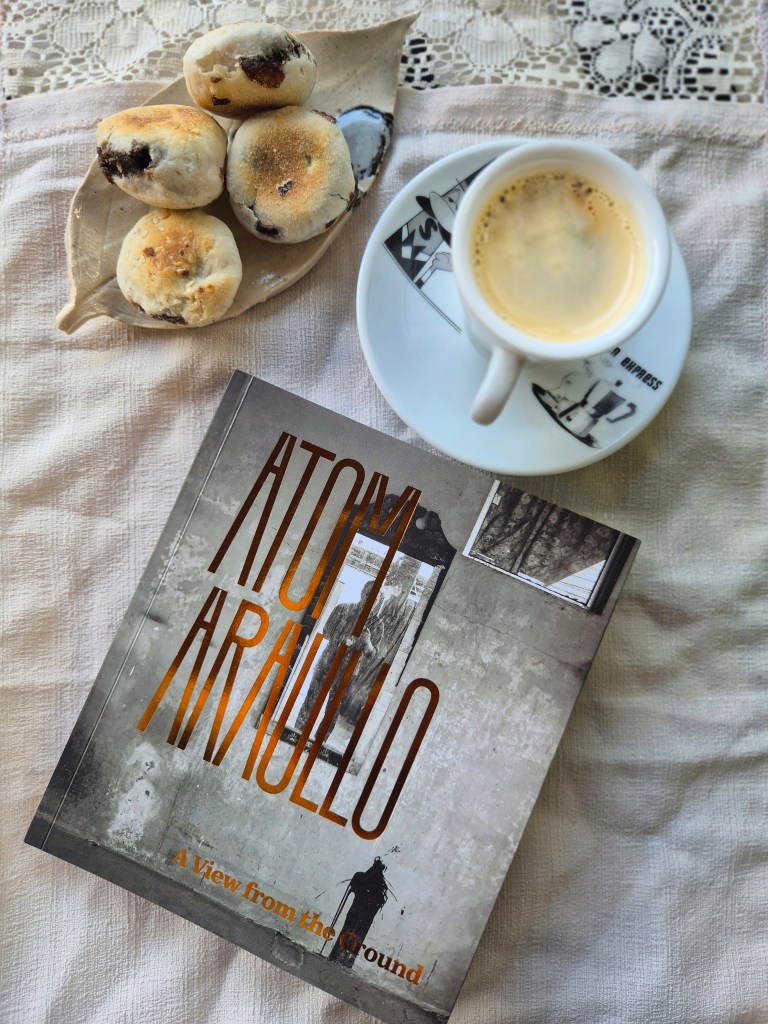

Atom Araullo’s A View from the Ground to drive me home. The one that hits closest to home, the one that dusts the sugarcoating off of being Filipino. A book that not only deserves to be put on the altar of Filipino essays, but to be taken, deeply, to heart.

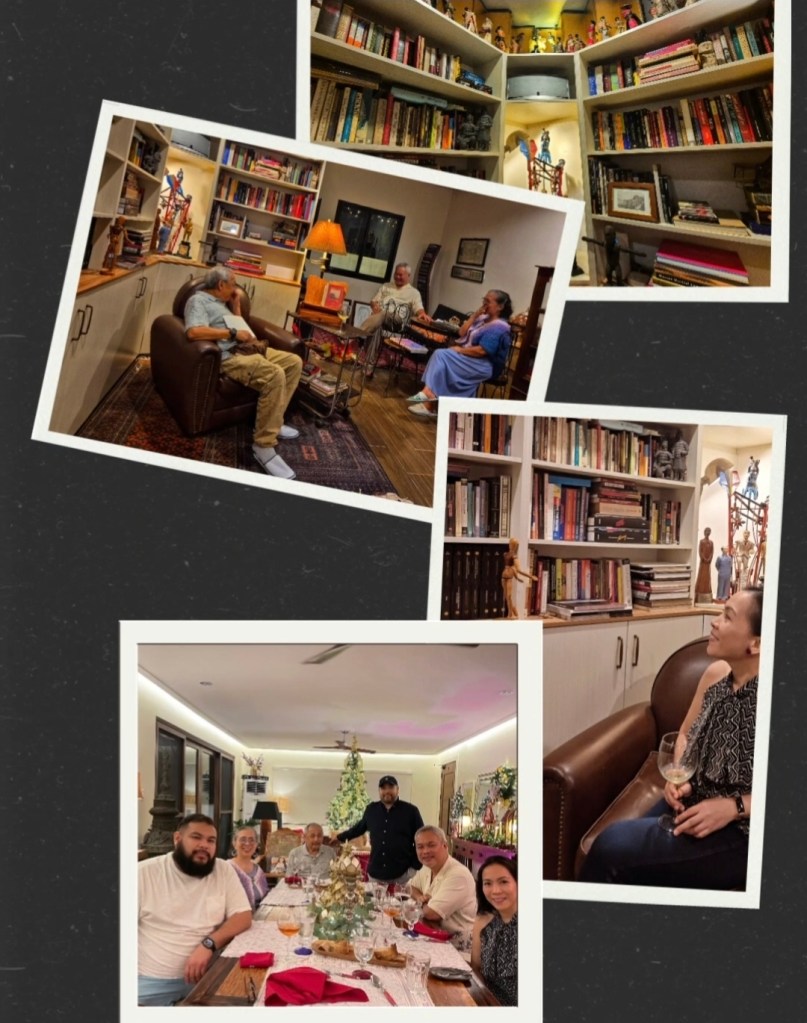

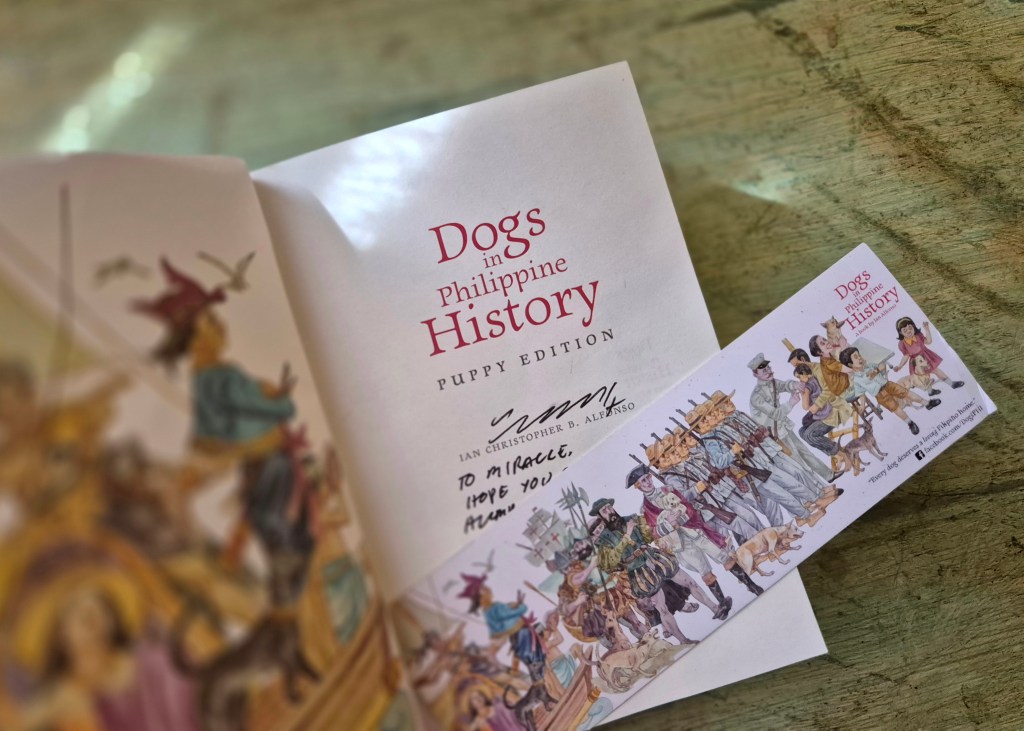

Speaking of home, a January highlight was an invitation to Balay Tawhay in my hometown. In that house by the sea, delightful conversations and original artworks by Arturo Luz, BenCab, Abdulmari Imao, Borlongan, et al, serve as appetizers for lovingly prepared feasts.

And they have books. Lots of books! Because really, how does one contrive to live without them?