“A small bookcaseful of the right books, and you are set for life.” — Rohinton Mistry, Such a Long Journey

Friends can tell when I have re-attuned to daily life because I become a bit scarce on social media, and I return to writing about (or not about, in the case of Vikram Seth) the books I have read.

This is the India-themed reading stack for June that has spilled over to July. Not too different from the way India spills beyond what you have allotted for it. India has a way of spilling over from a journey and into a life.

But it’s time these books are homed into the sections where they belong, in close proximity to each other, in a library organized by political geography. And I can’t do that without at least writing a few lines about each one.

These particular books deserve exhaustive reviews, but for the time being, I will have to be content with abridgments of why they accompanied me on my trip and what I loved best about them.

Such a Long Journey, Rohinton Mistry

Several Mistry volumes wait on my shelf. And yet, this is my first time to read him. I was not sure where to begin. All I instinctively felt was that a Mistry perspective was necessary for a more encompassing idea of India. I ended up choosing his first novel. It was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1991.

Contemporary Indian literature that come my way overflow with the repercussions of British colonialism, the partition, or the relationship of India’s Muslim and Hindu populace. But this is a seldom explored perspective of India’s modern history through the Parsee experience — an exciting realization for someone who is enamored with Iran! (As most of us know, Parsees are descendants of Zoroastrians from Persia who fled to India as a result of the Arab Conquest.)

It is set in 1971, the year of the Indo-Pakistani war and the Bangladesh Liberation War. Centered on Gustad and his family, this is a story of ordinary lives enmeshed in extraordinary times. It teems with the humor, the pains, and the realities of living. This is a book for readers who do not skim over the prose but find beauty in taking time to appreciate details pregnant with cultural understanding.

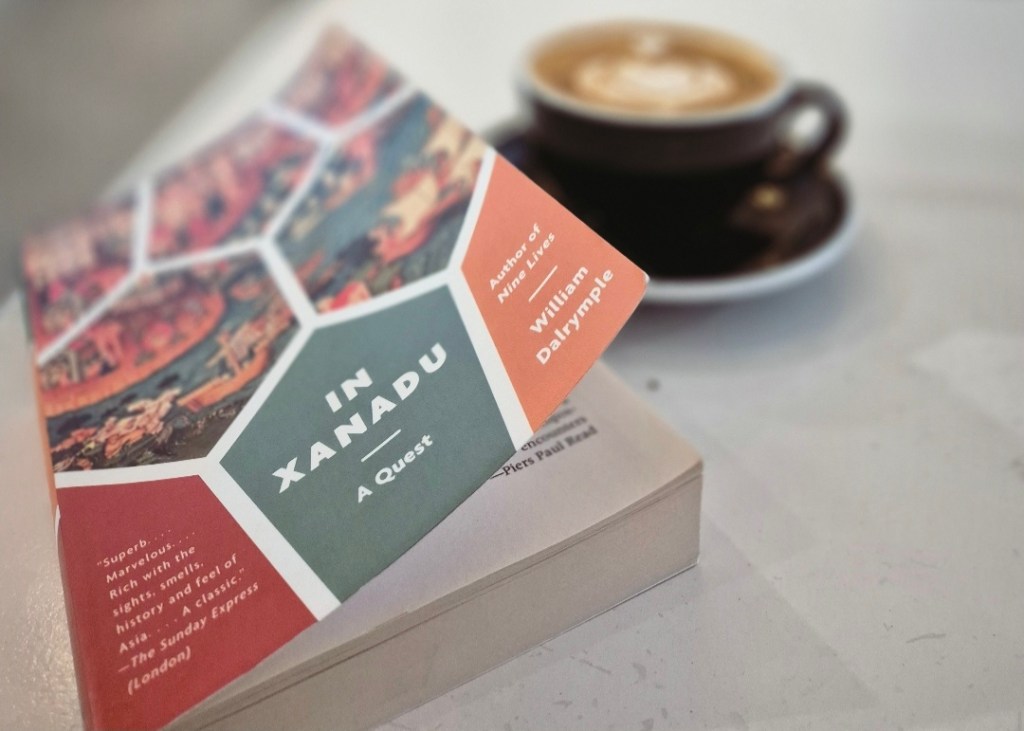

Nine Lives: In Search of the Sacred in Modern India, William Dalrymple

William Dalrymple’s name is often identified with lyrical prose and India, so this choice does not need any expounding. Although I was wrong in thinking it would be an easy read. I thought it would not be too emotionally affecting and would balance out the heavy themes of The Raj Quartet. Three stories in, I was already sniffling and wiping away tears inside my room in a Jaipur haveli.

This resulted in the decision that I would not read the nine stories straight, that I would read them in-between other books, in between deep breaths, in between exploring the land in which these stories are set, and that it would be the book I’d carry in my sling bag throughout my whole stay in India.

The nine lives that Dalrymple immortalizes from his travels flow from a pen of empathy and genuine curiosity, always with the intention to “humanize rather than exoticize”. It is a portrayal of nine characters that break free from standardized religions, and which represent different sects and personal beliefs that the author hopes to have escaped “many of the clichés about ‘Mystic India’ that blight so much of Western writing on Indian religion”; they are also manifestations of how, despite the exponential rate of change and modernization in the country, an older and more diverse India survives.

It is a book I would highly recommend even to those who are not planning a trip to India. Its lessons in faith and tolerance are relevant and enduring.

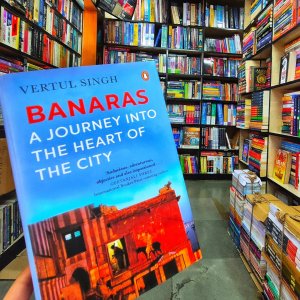

Jaipur Nama, Giles Tillotson | Banaras, Vertul Singh

“There is a beautiful word in Bengali — boi, which literally means a book. The word was commonly used in the vernacular for cinema and later came to be picked up by the Bengali elite while referring to an artsy movie and continues to be used to imply films. It has a deep connotation in that cinema is not just seen, it is also read. While walking through a city, one also reads it…” — Vertul Singh, Banaras

These two books have these in common: I purchased them from independent bookshops in Jaipur; they concentrate on a single city in India as the subject for the entire book; and they are books a reading traveler would benefit from tremendously when traveling to Jaipur or Varanasi.

While I learned so much about Jaipur from Tillotson’s Jaipur Nama, was thoroughly entertained by it, loved the passages on Jaipur’s architecture, and saw with my own eyes the wonders described in its pages, I was inscrutably drawn to the tone of Singh’s Banaras. There seemed to be an imploring strain that made itself heard to me, beckoning me to Varanasi, waiting for me to read the city beyond book pages, asking me to look into its soul.

Pyre, Perumal Murugan

Rajat Book Corner’s shelves were cascading with the best selections. They had Pamuk, Mahfouz, Proust, recent literary prize winners, the Indian greats, among many others. So you can imagine the argument between my other selves against the practical one who kept whispering firmly, “Just one book, just one book.”

After a while of intense internal struggle, I finally went with something I hadn’t seen in Philippine bookstores: Pyre, a 2023 longlister of the International Booker Prize written by Perumal Murugan.

“Good choice,” said the man at the counter.

“Thank you,” I answered, thinking it was something he always said to bookstore clientele.

“It’s a great book! We discussed this in our bookclub.” That’s when I realized he meant it. He had read Pyre. To my surprise, he added, “Wait. I think this is a signed copy. The author signed it when he came here.” And indeed, it was!

Pyre was the only book from this stack that I was able to finish reading within 24 hours, but the ending left me stunned for days!

This is powerful storytelling, but it is, by no means, a pleasant read. It feels claustrophobic and asphyxiating: But that’s how prejudice is. That’s how ignorance and intolerance feels. That’s what hatred is.

The Raj Quartet, Paul Scott

And now, the portion of this stack that took me longest to finish — The Raj Quartet: Four volumes of what is often declared as the nonpareil narrative of the dissolution of the British Raj.

The claim was convincing enough for me to take the massive tomes along for the ride even if that was all I heard about it. As I slowly turned page after page, I increasingly understood that it is necessarily heavy. It is, as Scott himself wrote, “The luggage I am conscious of carrying with me everyday of my life — the luggage of my past, of my personal history and of the world’s history.”

In Hilary Spurling’s introduction, she writes, “Scott did not condone the Raj. He looked long and hard at its many failures, its inhumanity, its smugness, self-righteousness and rigidity.” And although it is written in a Tolstoyan sweep, it finds a Filipino parallel in Linda Ty-Casper’s The Three-Cornered Sun in the way it shows how India’s War of Independence was not merely a confrontation between the Indians and British, but also between British and British, and between Indian and Indian. Scott lays open the lives of the unrecorded men and women, the lives that fall under the gray shadows, the ones “historians won’t recognize or which we relegate to our margins.”

Imagine this, a sketch. The first volume an outline on which Scott would continue to color and add contrast in the succeeding volumes, peopling it with new characters and adding the Second World War as another layer of complexity against an already rich and tumultuous Indian tapestry.

The first page of Volume I reads, “This is the story of a rape.” Reading about rape is not something a solo female traveler would intentionally do on a trip. But I was astonished by how Scott’s writing carried me through anyway. It made Volume II inevitable, wherein, all of a sudden, the characters became so fully dimensional you could touch them!

It was not lost on me that the first two volumes ended with two women giving birth but with grave consequences on the women. A metaphor for the birthing of nations, perhaps? Volumes III and IV continued to consistently reveal the multifacetedness of human beings, of nations, of identity, and of history. By the end of it all, I could only close my eyes, sigh, and try to take it all in, then whisper to myself, “What a journey!”

Rohinton Mistry’s Gustad once wondered, “Would this journey be worth it? Was any journey ever worth the trouble?”

Whether the question refers to journeys in literature or other lands, you won’t really know the answer unless you take it. Take it.