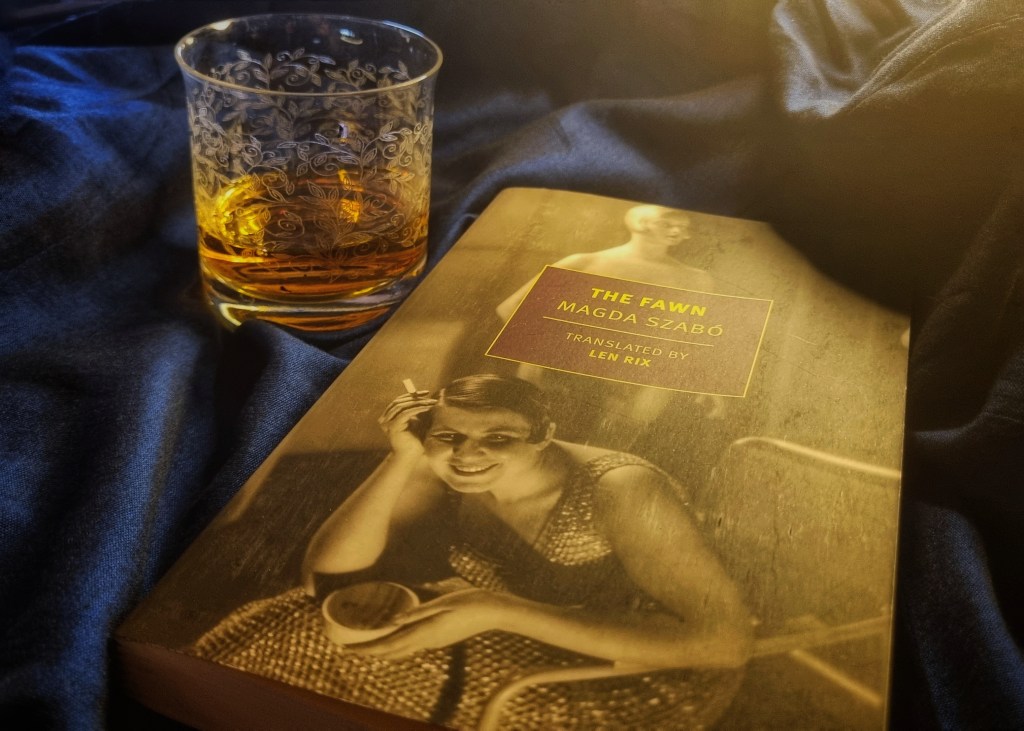

“I wanted to be with you sooner…” This first line, a faint melody, I imagine played by a solitary piano. This unwavering, melancholic undertone, suggesting that Eszter Encsy is addressing someone who is no longer in her life.

There is a calm, almost cold, but delicate aching to be accepted and understood. Recollections of childhood come across as confessions and explanations… including that time she did not mean to kill the fawn.

But how did that seemingly dispensable incident earn the title of the book? Perhaps the fawn is meant to symbolize the fragility of youth, and how easily it can be broken.

Magda Szabó, who died with a book in her hand, has bequeathed to the world novels that aim straight for the soul. She wrote of women; women who do not have to be faultless. She did not demand heroics from them or for them to be worthy of admiration or to be idealized. She only asked that they live — live intensely, and learn.

And yet, I did not expect her to go to the extent of Eszter. The moral puzzles are not vague here, it is made quite clear what kind of person we have as a central figure right from the beginning: “I could never have undertaken to be a good girl and never to tell lies…” “I lie so easily I could have made a career out of it…” “I was also laughing at the monster I really am…” “I wasn’t a very nice person and I wasn’t very friendly…”

We immediately get the picture. Appalled, we double-check the synopsis, even though Szabó readers know that her synopses hardly describe what one encounters between the pages. But we read on. Because Szabó is brilliant. Because we suspect that a gut punch or two awaits round the bend. Because oftentimes, nothing is what it initially seems. Because she writes of those difficult spaces between people that most of us are too inattentive, too timid, or too unimaginative to explore. Because we know that behind all her stories is a carefully woven leitmotif of a history she mourns. Because Szabó is always subtly reminding us of consequences, of how we cannot extricate our personal histories from that of our nation. Because she is eternally thought-provoking, and therefore, rewarding.

…and because those elegiac strains from that lonesome piano will linger long after you’ve turned the last page.