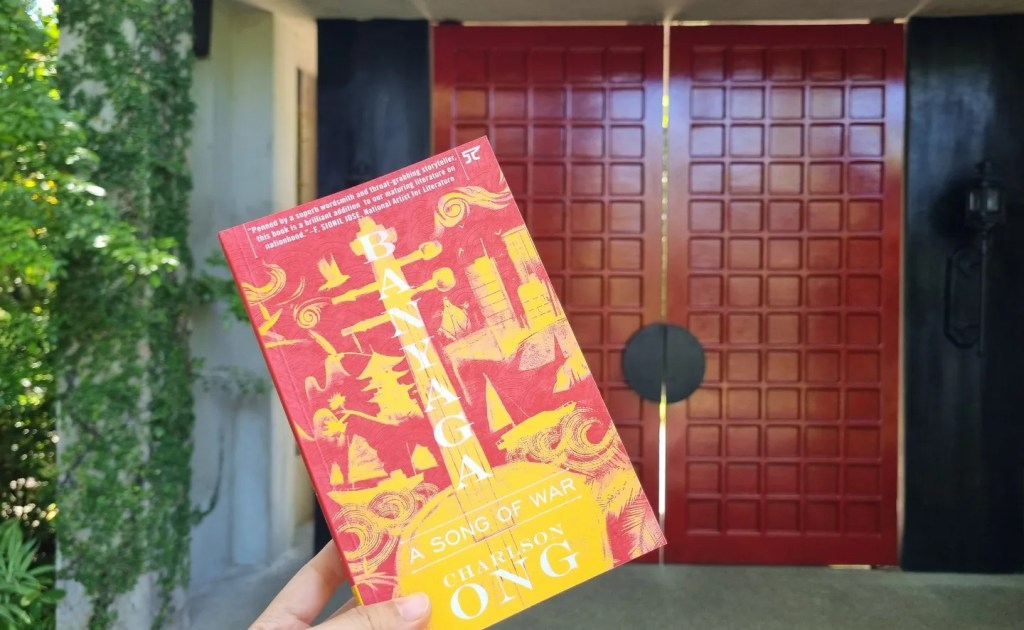

Stunning. Cinematic. Unforgettable.

Banyaga: A Song of War weaves melodies, threads, saturated shades of scarlet, unattainable indigo, and moonlight yellow into the rich literary tapestry of our nation, and gives prominence to an underwritten perspective of Philippine history and literature — that of the Tsinoys, the Chinese Filipino.

The vivid imagery (beginning with Chinese boys caught in a brawl that results in a sworn brotherhood, on a ship heading for Manila) that remains consistent up to its plaintive ending in Manila Bay almost a century later; the fleshed-out personalities and exuberance of the characters; and the nonlinear narrative, brilliantly interlaced throughout the American occupation until the post-Martial Law era, tempts the mind’s eye to read this with a Wong Kar-Wai filter. With the acculturation of Chinese and Filipino traditions, and the subtle exposé on the workings of the government, economy, and political unrest as a backdrop, all of these lend to it a fullness of texture and quality that I have yet to encounter in any other Filipino novel published in the 2000s.

Banyaga, which means “foreigner” in our language, follows the lives of Ah Puy, Ah Sun, Ah Beng, and Ah Tin who hoped to escape poverty and political turmoil in China. Their dreams for better lives are soon trumped when they are rejected by relatives and family upon their arrival in Manila. As they are forced to fend for themselves and survive in a strange land that would become their only home, they will come to be known as Hilario Ong, Samuel Lee Basa, Antonio Limpoco y Palmero, and Fernando de Lolariaga. The different surnames suggest that the trajectory of their lives takes different turns, but an invisible thread would always bind the lives of the four sworn brothers and their families to each other and the course of Philippine history.

This novel has indelible scenes that will have you gasping in shock, push you on the edge of your seat, and break your heart repeatedly throughout the span of three hundred and seventy-three pages, but most of all, it will lead you to ponder on nationhood and leave you in awe of the heights that our nation’s literature has achieved.