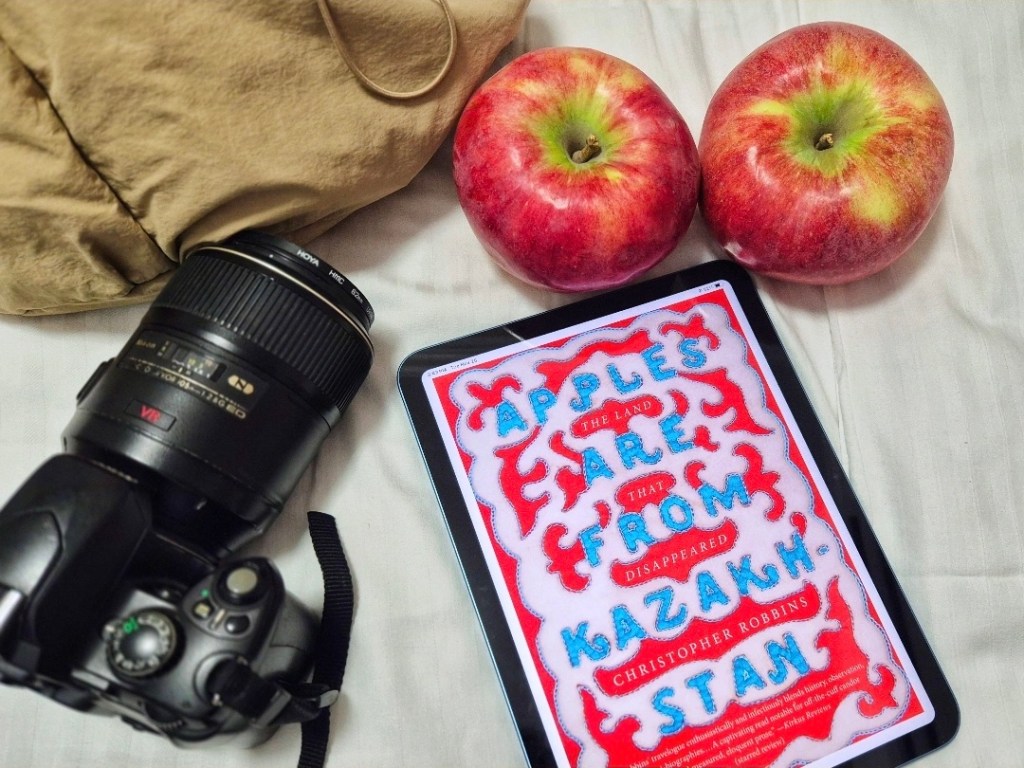

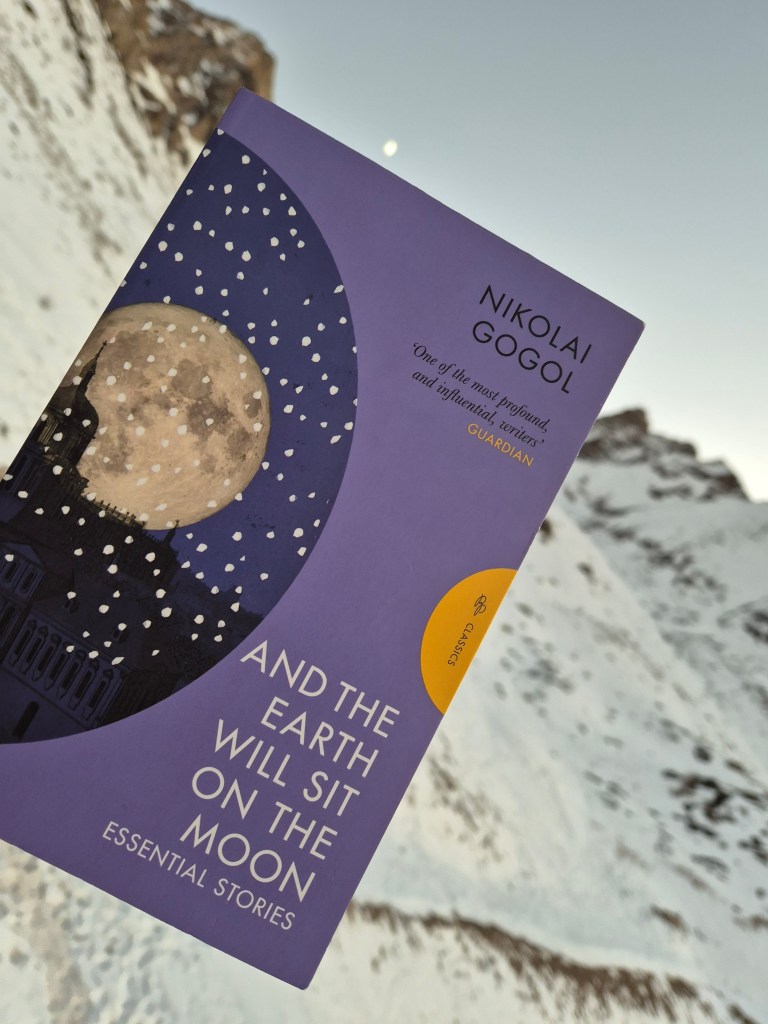

That was me. The girl with a Gogol anthology poking out of a backpack pocket while walking the length of Almaty’s Gogol Street a number of times, earning her more than 20,000 steps a day;

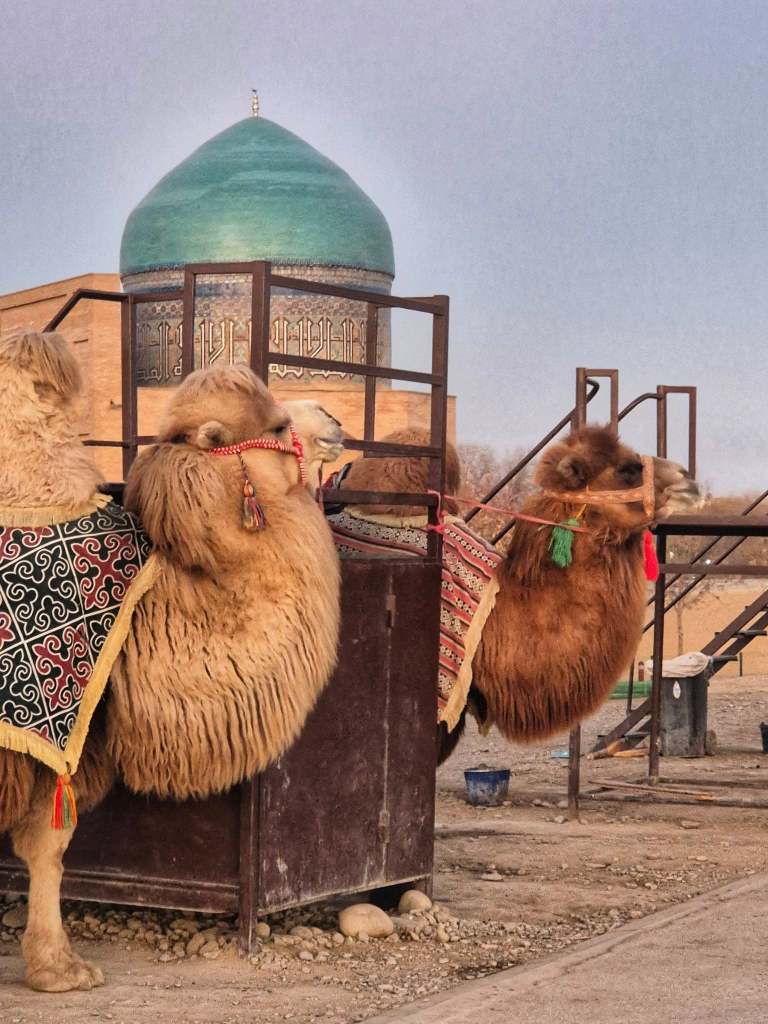

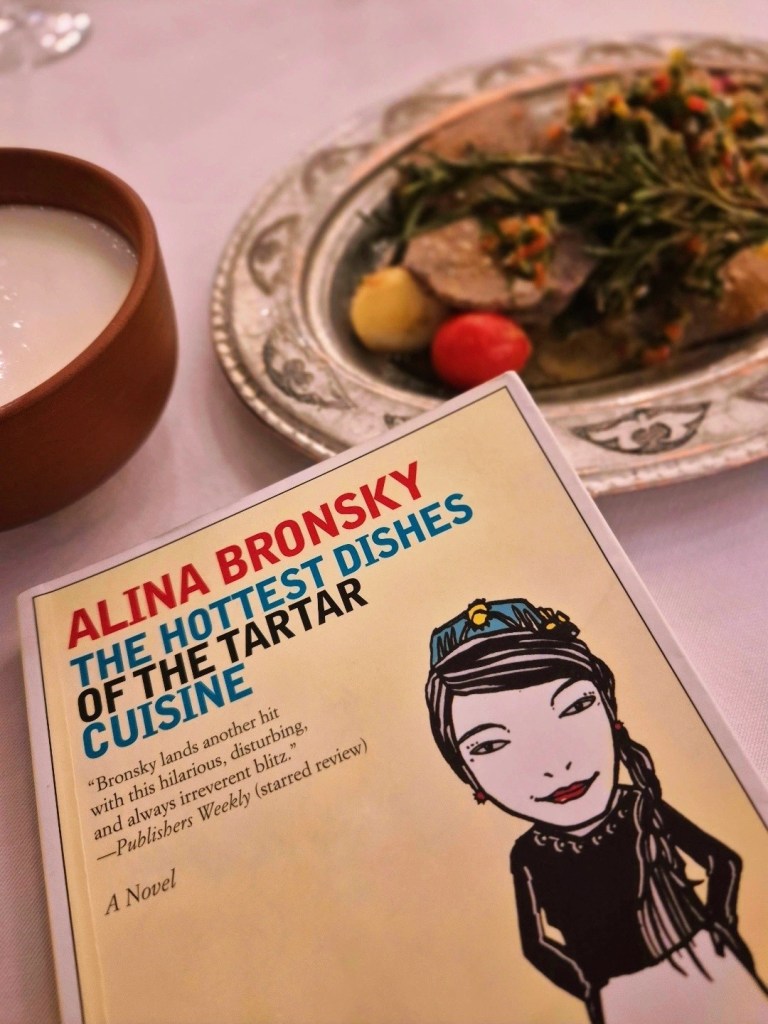

who paired her first Kazakh meal of horse meat and fermented camel’s milk with Alina Bronsky’s insane but unexpectedly touching Hottest Dishes of the Tartar Cuisine;

who carefully savored the nuances in every Kazakh story from Amanat (Women’s Writing from Kazakhstan) on every fermata between adventures, and upon completion, discovered that it would be one of her favorite collections of short stories;

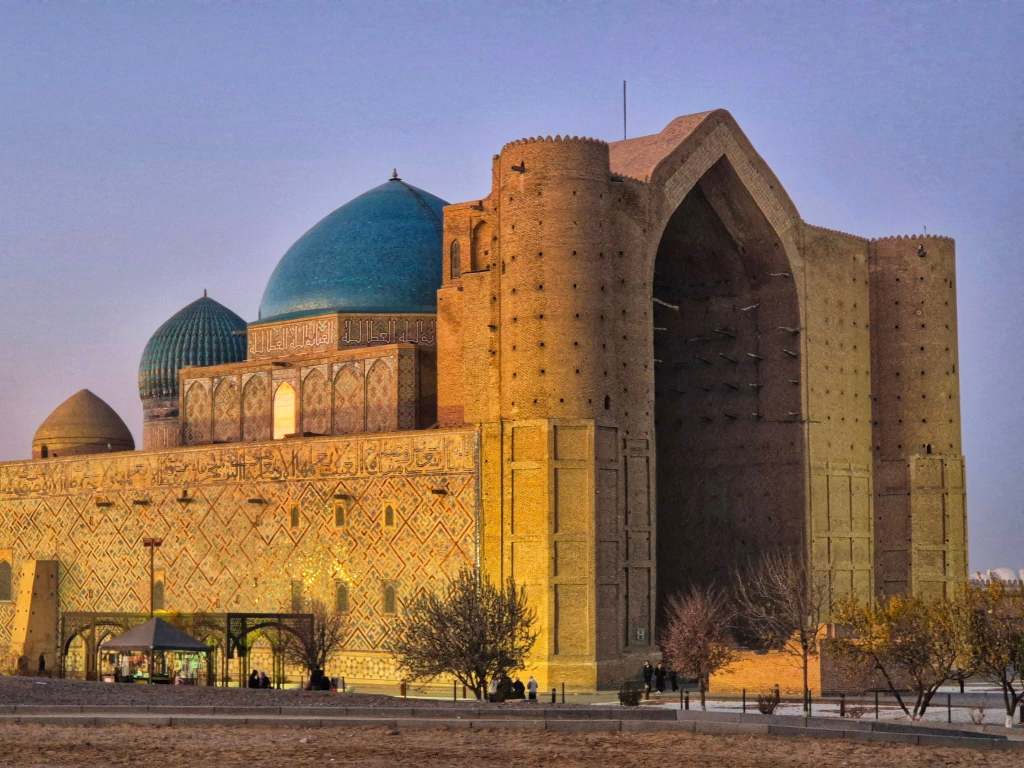

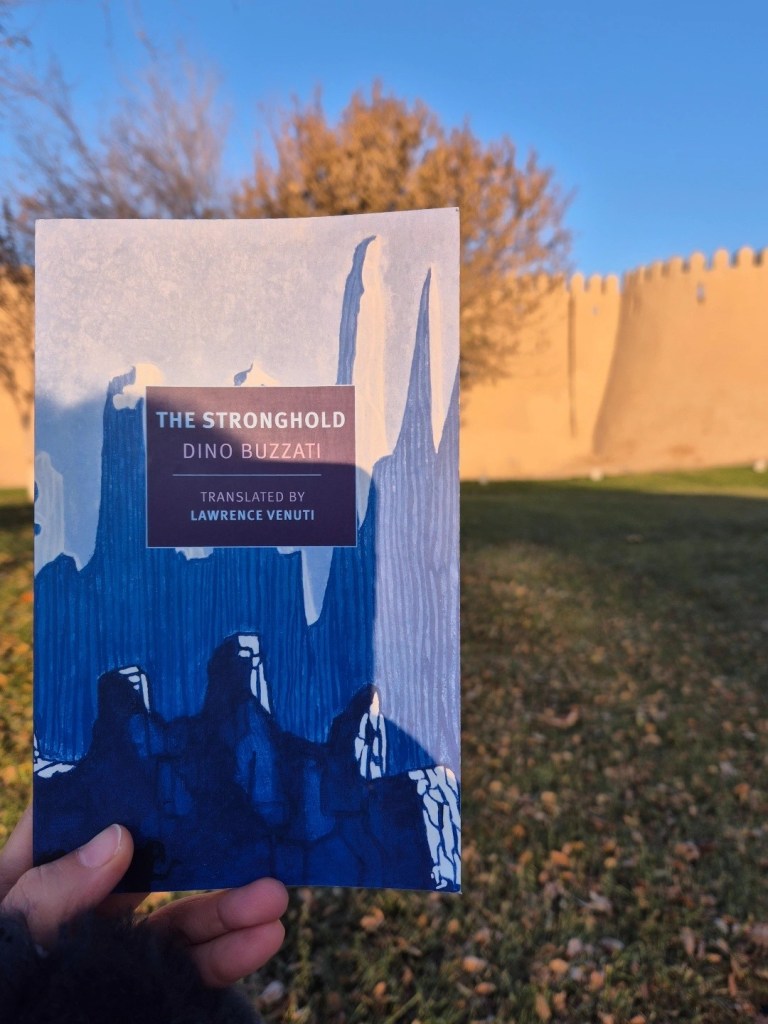

the girl who brought Buzzati’s The Stronghold (aka The Tartar Steppe) to a stronghold in a Tartar steppe, and who realized that Buzzati would have been happy with her for taking a cue from his novel and living a life contrary to that of Drogo’s;

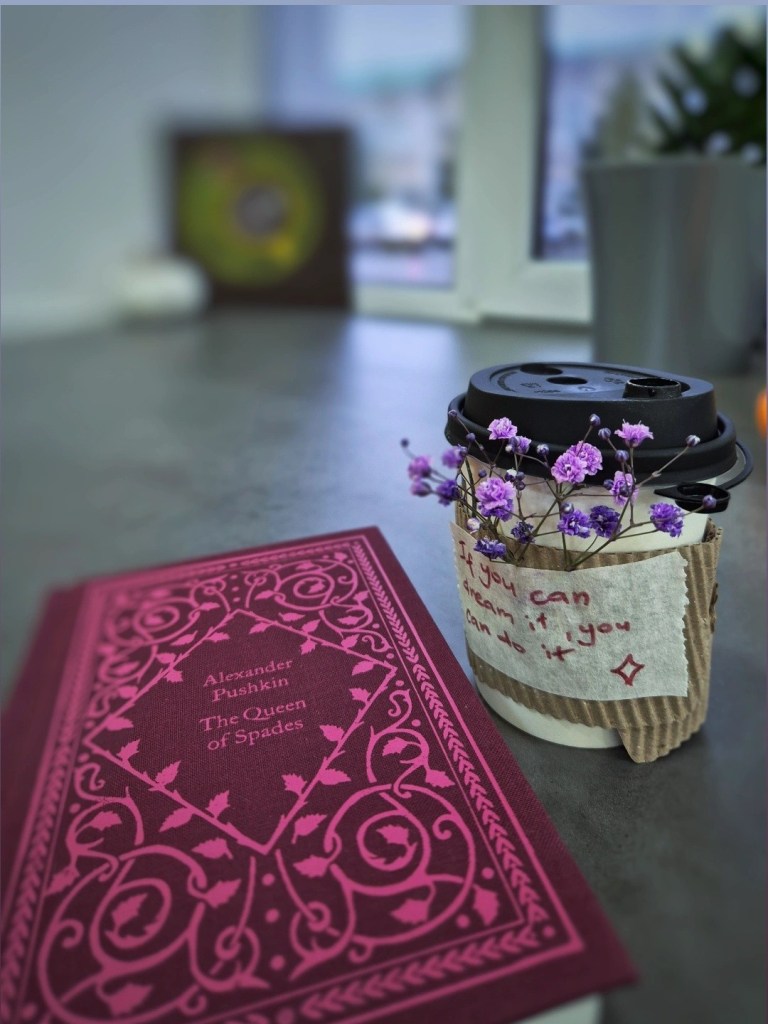

the girl who felt like a queen when she received a cute note in English with tiny flowers from a barista in Uralsk, and a free pass at the Pushkin Museum by reading and bringing The Queen of Spades with her;

who learned about Pugachov’s Rebellion through Pushkin before knocking on Pugachov’s door;

who reunited Dostoevsky’s Notes from a Dead House with Kazakhstan simply because it’s where he started writing the notes;

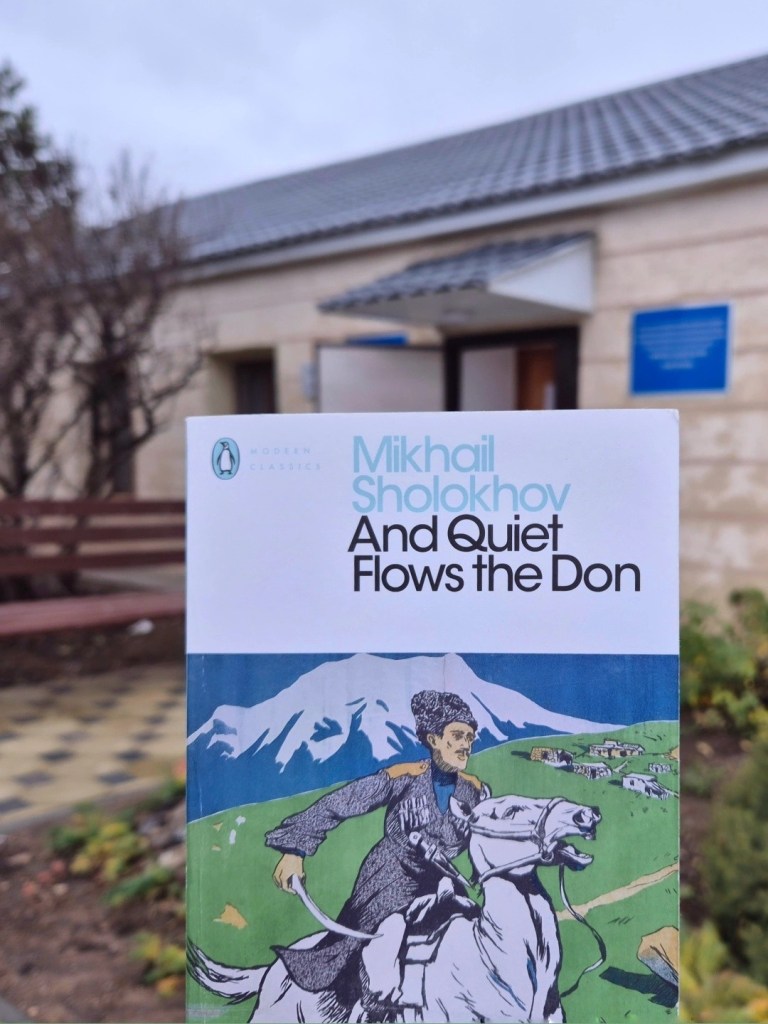

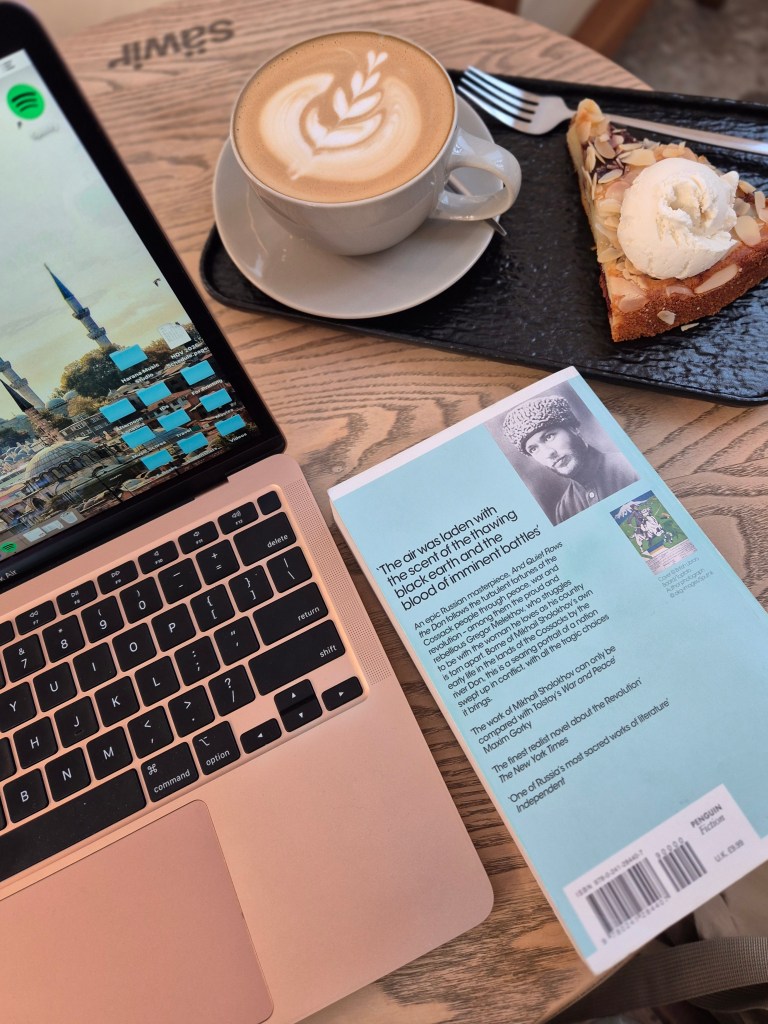

the girl who wished she flowed, but instead, lumbered through Sholokhov’s epic “And Quiet Flows the Don,” and being devastated by it, could only take the hefty book to the house where Sholokhov learned that he was awarded the Nobel and play a plaintive melody on his piano while gazing at his portrait, wanting to ask him so many questions;

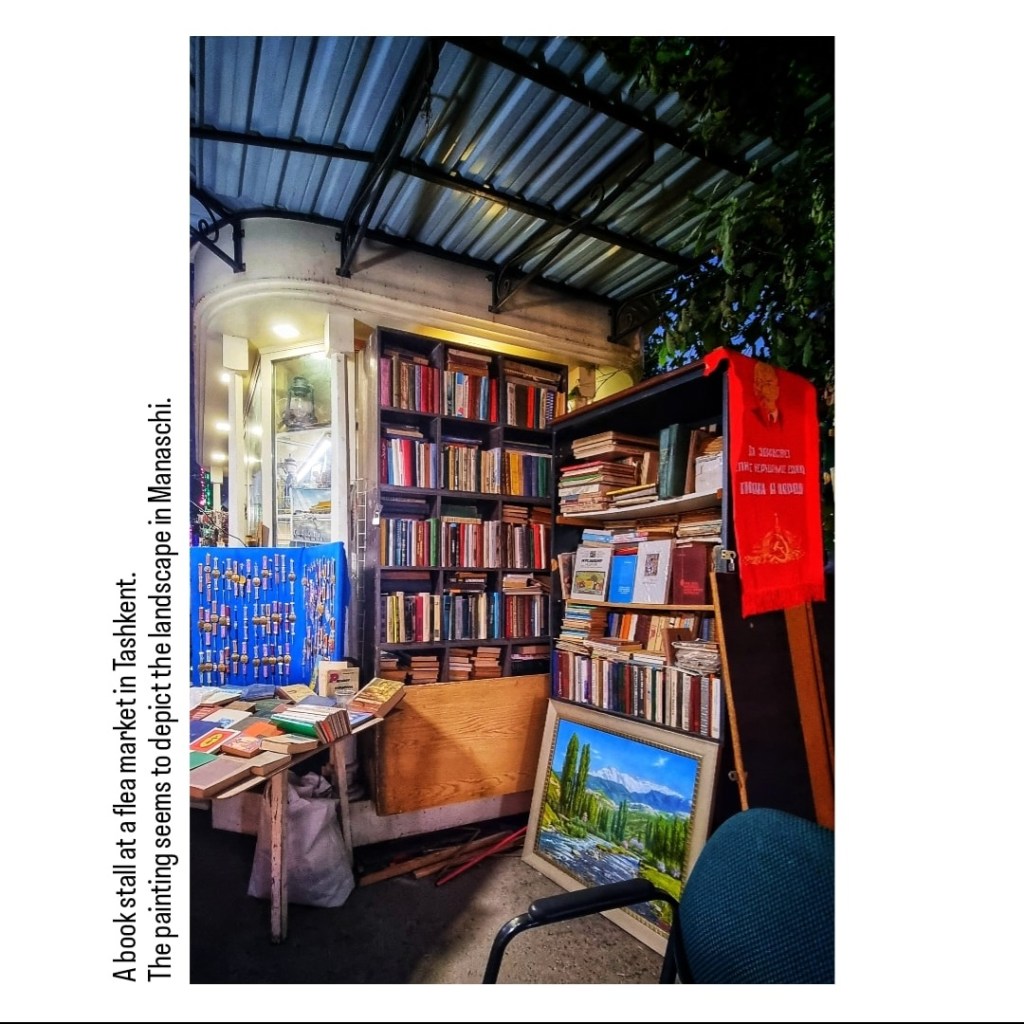

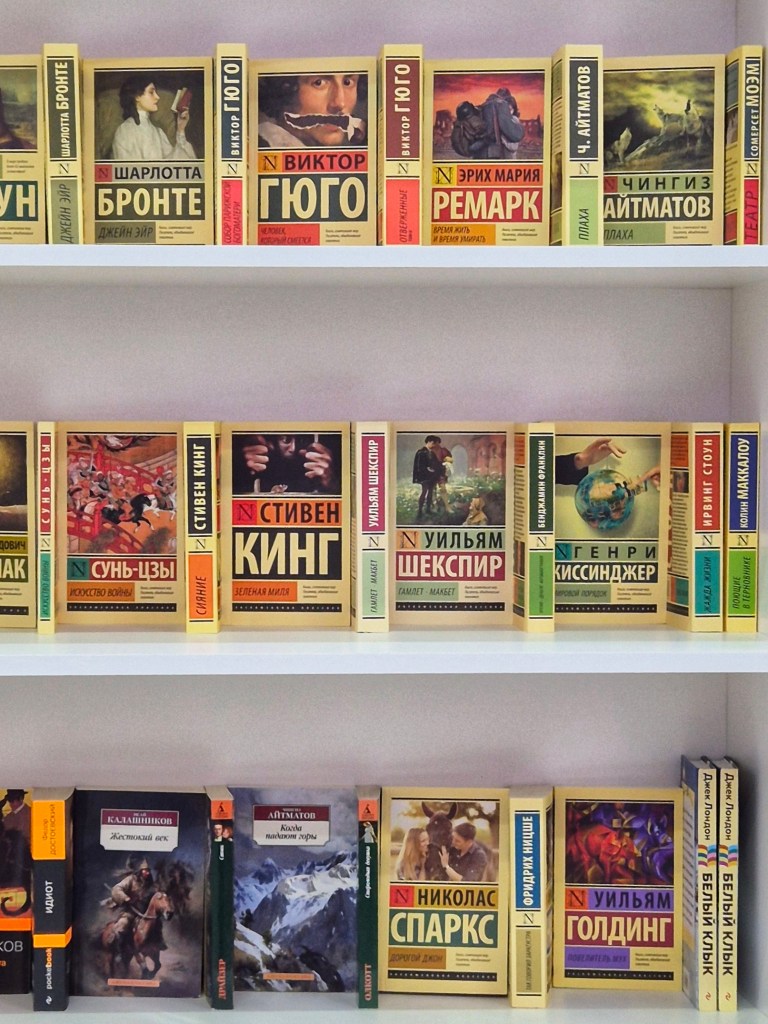

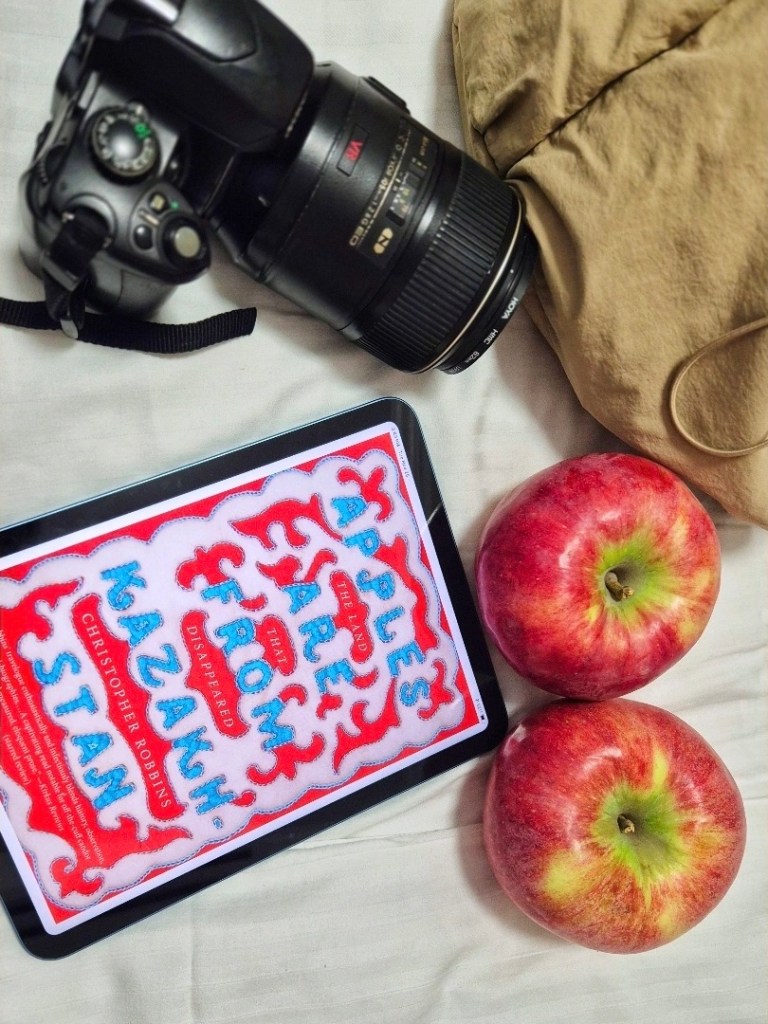

the impractical girl who carried all these books to a trip, thankful that she did because Kazakh bookstores humble the English reader by catering only to the Kazakh and Russian reader;

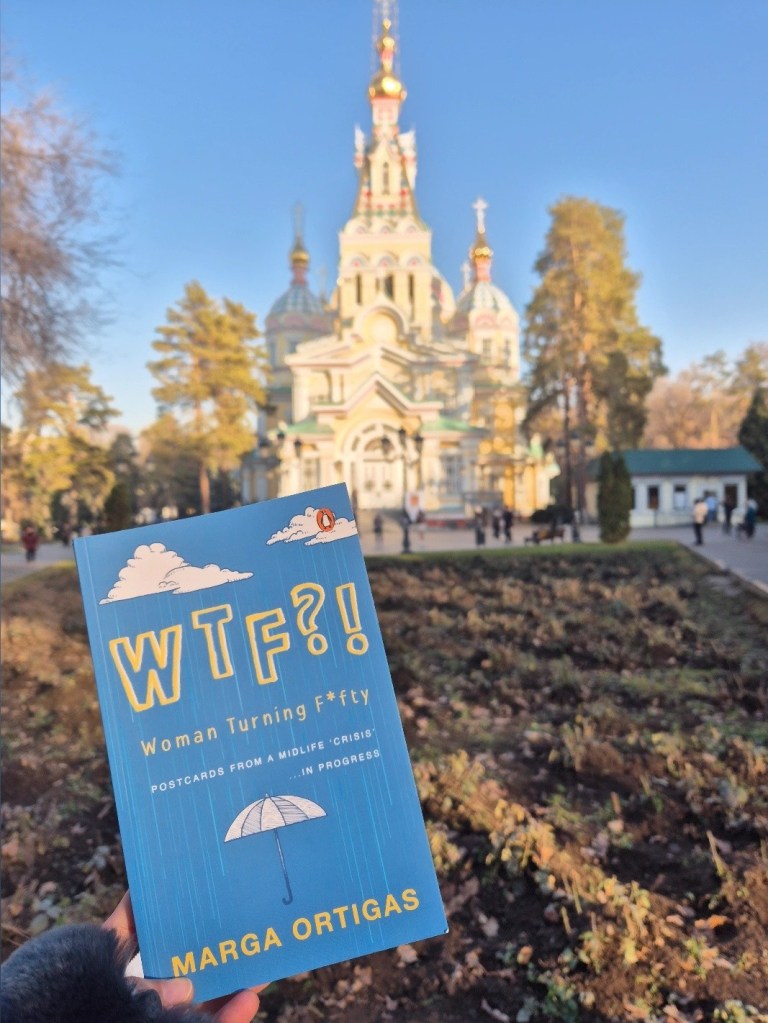

the girl who agreed with Marga Ortigas who wrote that reading is, “A special gift that showed you how much of the world still lay beyond the safety of your comfort zone”;

the girl who believes that traveling is one way of acting upon that gift.