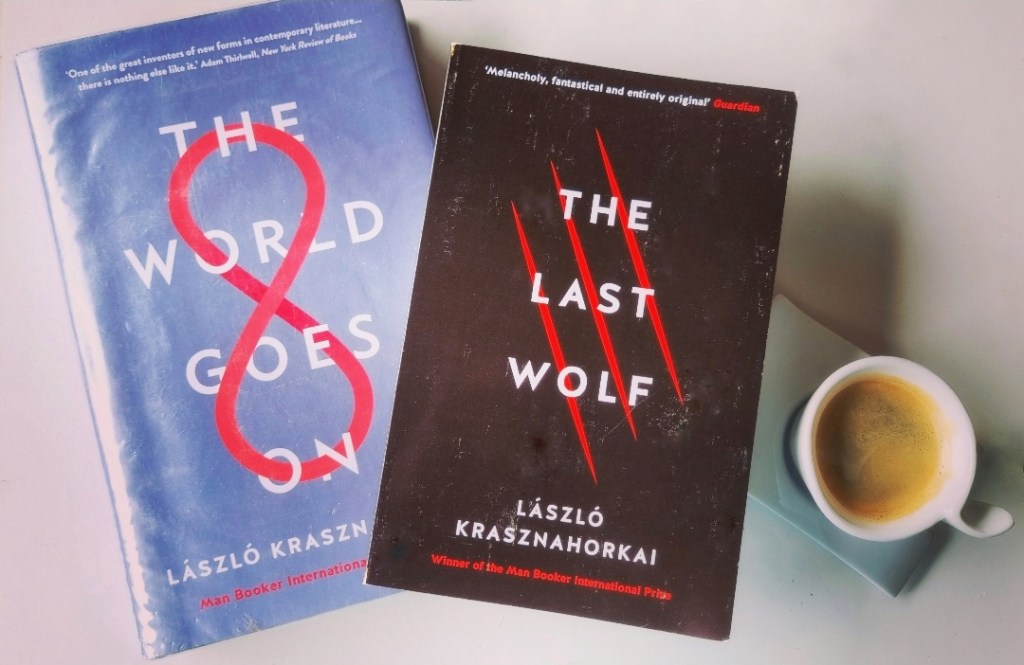

As if in sync with my protracted pace in gathering enough courage to take on a Krasznahorkai, it also took a while for my order to arrive.

When at last his books occupied the Hungarian section of my shelf, I timidly went for The World Goes On to sample one of the short stories. Catching the name of my favorite city in the table of contents, I immediately turned the pages to The Swan of Istanbul.

The Swan of Istanbul (seventy-nine paragraphs on blank pages)

In memoriam Konstantinos Kavafis

My excitement was fueled upon seeing it dedicated to the writer of my favorite poem! (Too excited, in fact, that my eyes skipped the words in parentheses.)

What greeted me was the literary counterpart of John Cage’s 4′33″. Blank pages, ladies and gentlemen.

These thoughts assailed me as I flipped through the emptiness of each page: Doesn’t Krasznahorkai have a reputation for composing entire books with a single sentence? Where was the intimidating muchness of which they spoke? Should I lazily call this pretentious without giving it much thought and expose my limited knowledge of post-modernism and deconstructivism? But also; László, I like you already.

And yet, after “reading” the blank pages, I closed The World Goes On and tried my hand at The Last Wolf. There I found the labyrinthine thoughts and lines for which he is known, a philosophy professor who thinks he is mistakenly hired to write about the last wolf of Extremadura, a wasteland in Spain that was once part of what the Romans called Lusitania, and yes, the solitary period at the very end.

As the story spirals out, the reader is made to ponder on the hunter and the hunted, how the two are very much alike and are part of the same thing; gentrification, not just among humans but among animals; bestiality and humanity intermingling; the incomprehensibility of existence, and how man is a prisoner of thought.

If John Cage’s 4’33″ was meant to be the embodiment of the composer’s idea that any auditory experience may constitute music, what if reading Krasznahorkai is to explore, to be surprised, to question what constitutes a reading experience, and to challenge what else literature can be?