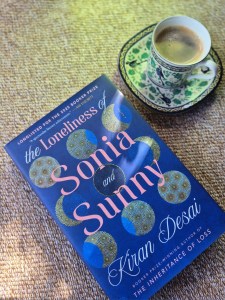

“Sonia’s heart was a Hopper painting.” The title is blunt about Sonia and Sunny’s loneliness, but it’s this Hopper line that makes one grasp how lonely: A profound loneliness that has something to do with a vulnerable and fluctuating selfhood, an abstract loneliness that is tied to urban and modern life, an existential loneliness craving real connection that cannot be quenched by mere companionship.

Lonesomeness was Edward Hopper’s leitmotif, and Kiran Desai weaves this theme into an unfolding raga: at times beautiful, at times disorienting, at times cruel and repulsive, at times disquieting, at times capriciously meandering.

I have no qualms with the length. Although considered massive in proportion to the contemporary reader’s short attention span, I imagine the typeface and the font size would make Tolstoy say, “Hold my vodka.” But the book often offers clues to Desai’s literary and artistic inspirations and subtly discloses why the author found its length necessary: “How many millions of observations and moments it had taken to compose this book!” Sonia thought about Anna Karenina.

It is not, however, “an unmitigated joy to read” as Khaled Hosseini claims in a blurb. Reading about Sonia’s toxic relationship with Ilan, the narcissistic artist, was nauseating to the point of causing an unpleasant physical reaction that made me want to give up one-third through the book. Although aghast, it was accompanied by the awe of how much the author fathoms an artist’s relationship with darkness. There is no question about this being a work of art, but I will admit that I hoped to love and enjoy this more than I did.

While Sonia and Sunny failed to endear me to them, I was drawn to Sonia’s mother, who kept company with books and understood that there are worse things than loneliness, and Sunny’s father, who desired to break free from the cycle of corruption in the family for the sake of his son, believing that to be honorable is to be free. While I was concerned that portrayals of men beyond the main characters would perpetuate stereotypes of Indian men, it was Desai’s keen eye for psychological and cultural detail, and her vast insight into the plight of the immigrant, that made me continue reading.

To paraphrase a memorable line from the novel: I knew when I saw this book that the story would not be simple. And simple it is not.