On a trip to Turkey in 2016, we landed at Sabiha Gökçen International Airport, which is on the Asian side of Turkey and closer to the Marmara Sea. The Istanbul Airport that opened in 2018 is on the European side, and just before landing on the meeting point of the world, one is gifted with a breathtaking view of the Black Sea.

I saw the Black Sea thrice from an airplane window on my most recent trip, and the irony dawned on me that this body of water that has sadly become the “largest mass of lifeless water in the world,” in fact, teems with so much history and so much… life!

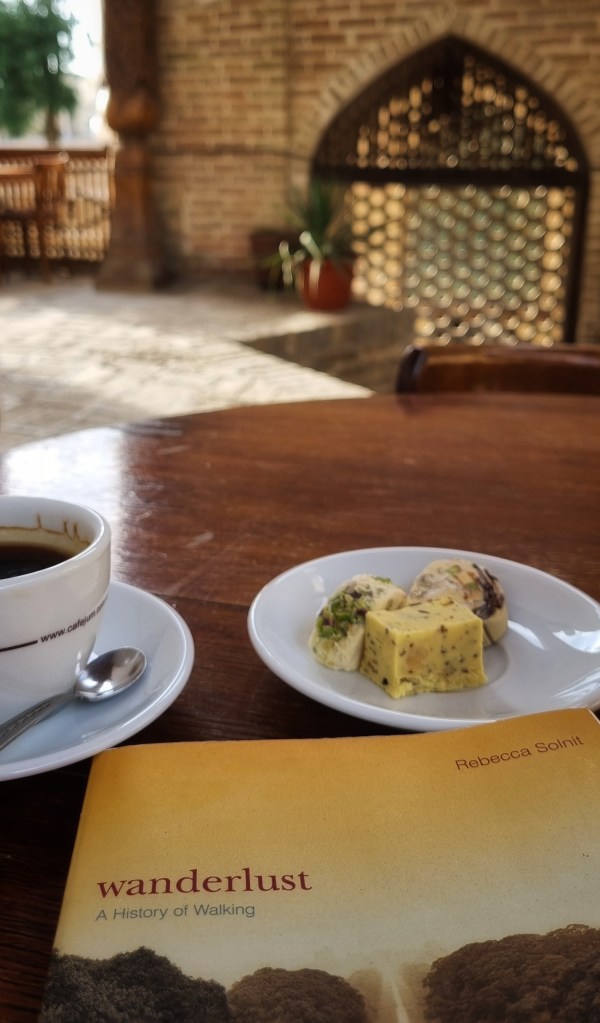

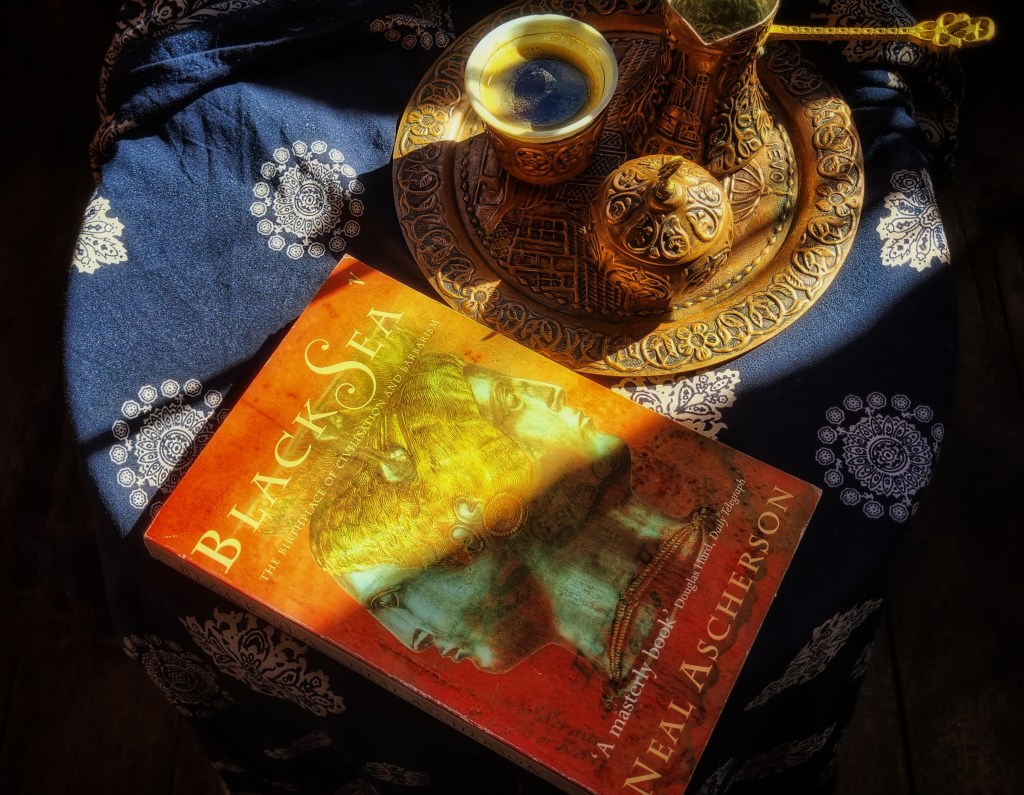

This book written by Neal Ascherson about this birthplace of civilization and barbarism accompanied me, although I only finished reading it on my way back home. I don’t think I’ve read a more poetic history book!

“Human settlement around the Black Sea has a delicate, complex geology accumulated over three thousand years. But a geologist would not call this process simple sedimentation, as if each new influx of settlers neatly overlaid the previous culture. Instead, the heat of history has melted and folded peoples into one another’s crevices, in unpredictable outcrops and striations.”

Reading it brought me back to the landscapes of Tokarczuk’s The Books of Jacob and to where I’ve just been, merging the lands of my dreams with those places that are the epicenters of current world events. Because somewhere in the midst of this all, is the history of the Black Sea.

From its first mention in literature in the Bronze Age (where Jason and the Argonauts sailed upstream the Bosphorus to the Black Sea); to the different Central Asian tribes and kingdoms; to chapters that made me understand better the Russian Revolution and Communism’s life, course, and death in that region; to the question of Crimea, Russia and Ukraine’s relationship and to many things in between, I am in awe of how Ascherson sustained a poetic voice!

In a way, it answers our suspicions about how, despite all the earlier discoveries of the East in almost all fields, the West is still seen as more superior and more “civilized”. It is an enlightening investigation on the definitions of civilization and barbarism that surprisingly touches on feminism and immigration, which is quite different from what most minds have been programmed to believe.

Here is a history book that does not merely record events and dates, but most importantly, relationships. For as the author compellingly reveals, the Black Sea is not just a place but a pattern of relationships, and nothing like the symbiosis of the Bosporus Kingdom has ever happened.

A beautiful thing about traveling and reading is to be able to measure ourselves against the expanse of time and history, with the intention of acquiring more perspective, if only to acquire more life.