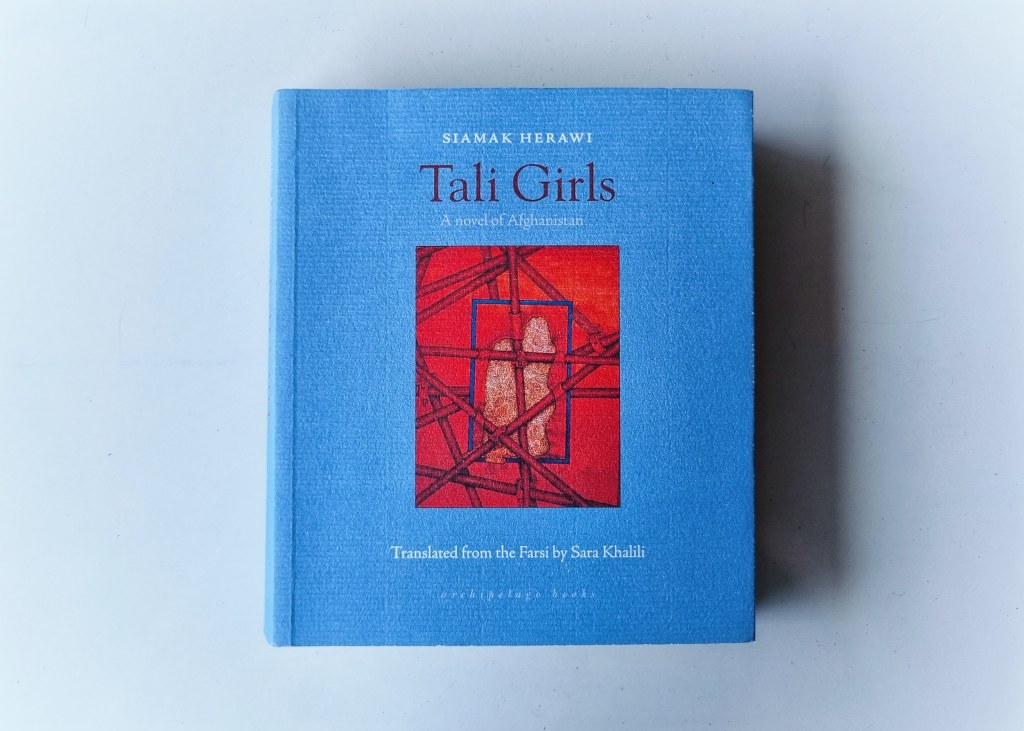

…because I would immediately pick up a novel of/from Iran without any prodding.

It took me almost halfway through to get into the book’s rhythm, however: Apart from being surprised that it is not set in contemporary Iran but pre-revolutionary Iran (and horrified to think that things have only gotten worse for women in post-revolution Iran), one main character irked me, and I kept weighing it up against another Iranian work of magic realism that remains unsurpassed in my books. But as I read on and the threads of the story came together, I came to appreciate Women Without Men for its own merits. It is, after all, about women overcoming hardships and breaking free from the conventions that Iranian society imposes on them. It is therefore no surprise that it was banned shortly after its publication.

The lives of Iranian women and the experiences depicted here are not isolated cases, and they bring to mind a line from Universal Compassion, an essay by Natalia Ginzburg: “We have come to recognize that no event, public or private, can be considered or judged in isolation, for the more deeply we probe the more we find infinitely ramifying events that preceded it…” Thence the problems that the characters face are not merely personal. In an ideal world, these are issues that an entire civilization must address.

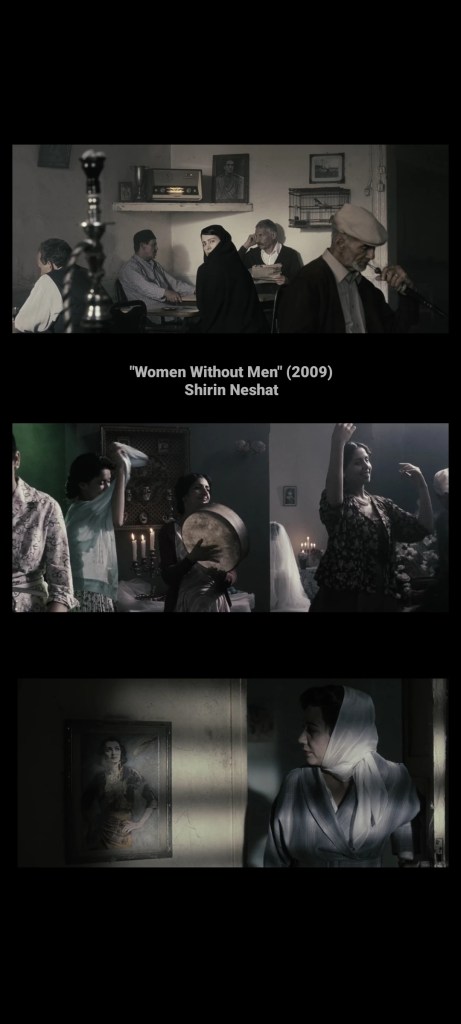

The book naturally ushered me to the screen adaptation. The director, who wrote the preface for this edition, worked closely with the author and the collaboration seems to have led to a beautiful fleshing out of ideas. Being a fan of Iranian cinema — because no one does cinema like the Iranians! — I am tempted to say that I like the film more than the book. But for an exceptional experience, allow me to suggest a book-movie-pairing instead; because what was ambiguous and abstract in the novel became poetry in the film; and if not for the book, there would be no film.