Tashkent, Uzbekistan

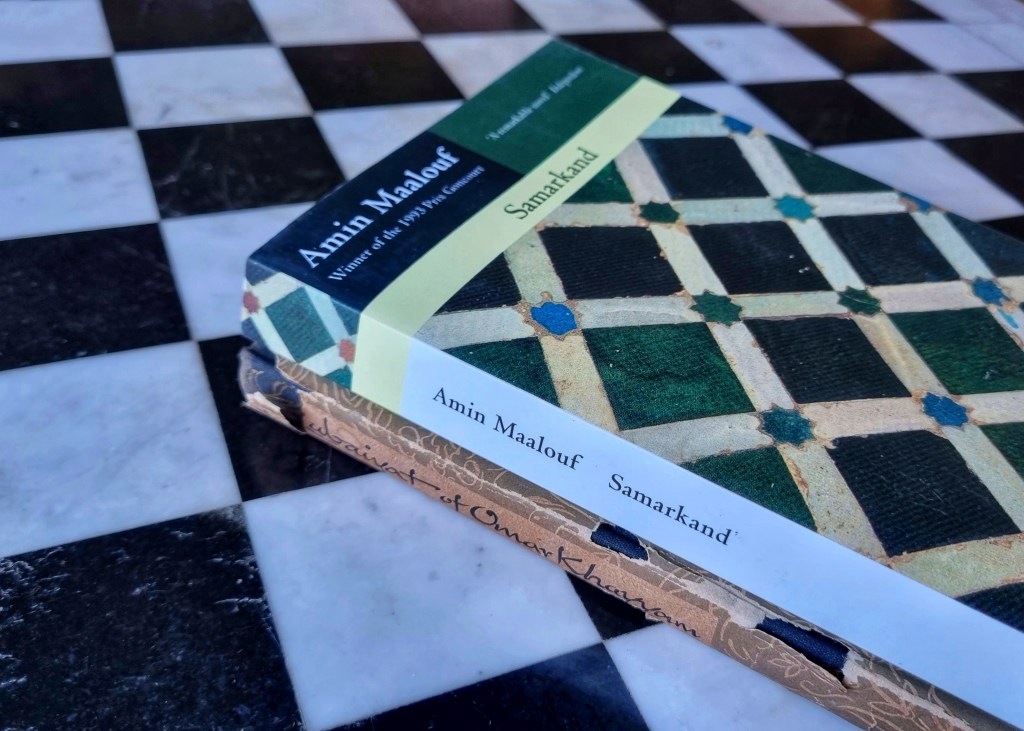

In which city did Alexander Solzhenitsyn miraculously heal from a stomach tumor that he chose the place to be the setting of Cancer Ward? Where did Mikhail Bulgakov’s widow hide the manuscript of Master and Margarita before it was published? To where did Anna Akhmatova evacuate during the Leningrad siege? For which city did Vronsky refuse an assignment significant to his military career in favor of Anna Karenina? In which city is the oldest Quran kept? Tashkent.

Tashkent Metro, Uzbekistan

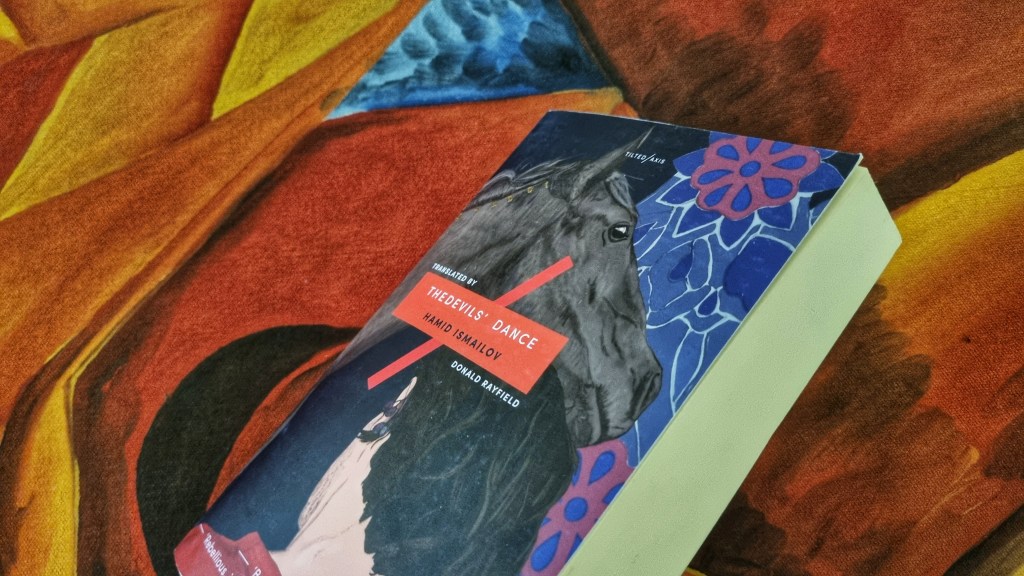

It has played important roles in literary history, and literary history seems to be woven along the threads of daily life here. Three of Tashkent’s Metro Stations that I was able to pass through today are dedicated to writers: Alisher Navoi, the greatest writer in Chagatai history; Abdulla Qodiriy, the nonfictional character of the novel, The Devil’s Dance, which I read earlier this year, and writer of what is considered the first Uzbek novel; and Alexander Pushkin!

National Library of Uzbekistan, named in honor of Alisher Navoi.

A baffled immigration officer at our international airport asked me, “Why Uzbekistan?”

This post is the first of a series of answers.