From Stefan Zweig’s Magellan, to Robert Graves’s Homer’s Daughter, to Aatish Taseer’s A Return to Self, to Kahlil Corazo’s Rajah Versus Conquistador, July seemed to have a fortuitous recurring theme in the books I read and in my encounters with storytelling: New ways of seeing and new ways of reframing self and history.

For someone whose nation regards as a hero the man responsible for Magellan’s death, I have to admit that this book was approached in Lapu-Lapu mode, en garde, expecting a Eurocentric view of history. But Zweig had me at page 11 upon acknowledging that the primary objective of the Crusades was to wrest the trade route barriers from Islamic rule. You don’t often get that admission from a Western book written in the 1930s.

In Philippine history, Magellan’s death eclipses the fleet’s first circumnavigation of the world. This book emphasizes the feat of an adventurer who had, at the time, “far outstripped all others in the exploration of our planet,” and proved beyond theory that the Earth was round. He was bad news for flat-earthers. Zweig humanizes the man whose death we celebrate, and this is a great read for those who would like to peer through another vantage point of the expedition. But dear Stefan, as much as I am a fan of your writing, Magellan did not “discover” the Philippines; he merely set foot on it and placed it on a Western map.

“What we term history does not represent the sum total of all conceivable things that have been done in space and time; history comprises those small illuminated sections of world happenings which have had thrown upon them the light of poetical or scientific description. Achilles would be nothing save for Homer.”

Speaking of Homer… how did I not know that the author of the more famous I, Claudius has penned a delightful book called Homer’s Daughter, claiming he could not rest until this novel was written after finding arguments on a female authorship of The Odyssey undeniable? It is based on the premise that The Odyssey — authored over a hundred and fifty years post-Iliad, more honeyed, civilized, and sympathetic especially toward Penelope — was written by a woman.

It makes for an enjoyable read as Graves imagines the life of Nausicaa, a Sicilian princess who rewrites Homer’s epic with elements from her life. “The Iliad, which I admire, is devised by a man for men; this epic, The Odyssey, will be devised by a woman for women. Understand that I am Homer’s latest-born child, a daughter.”

We have understood through the likes of Virginia Woolf that “for most of history, Anonymous was a woman,” but how the poet of The Odyssey could be a woman is a concept new and fascinating to me.

What if The Odyssey’s notion of Ithaca holds sway because it was not written by one who wandered off, but by one who stayed?

And yet, Aatish Taseer’s Ithaca remains my kind of Ithaca: “The pilgrim spirit is one that wanders away from the comfort and safety of our home secure in the knowledge that the transformation the pilgrim will undergo over the course of his journey is the destination.” The author has a life story incredible enough, but more importantly, here’s a writer and traveler who shows us how profound traveling can be when we are mindful of the inner journey. A Return to Self is a book I will be returning to.

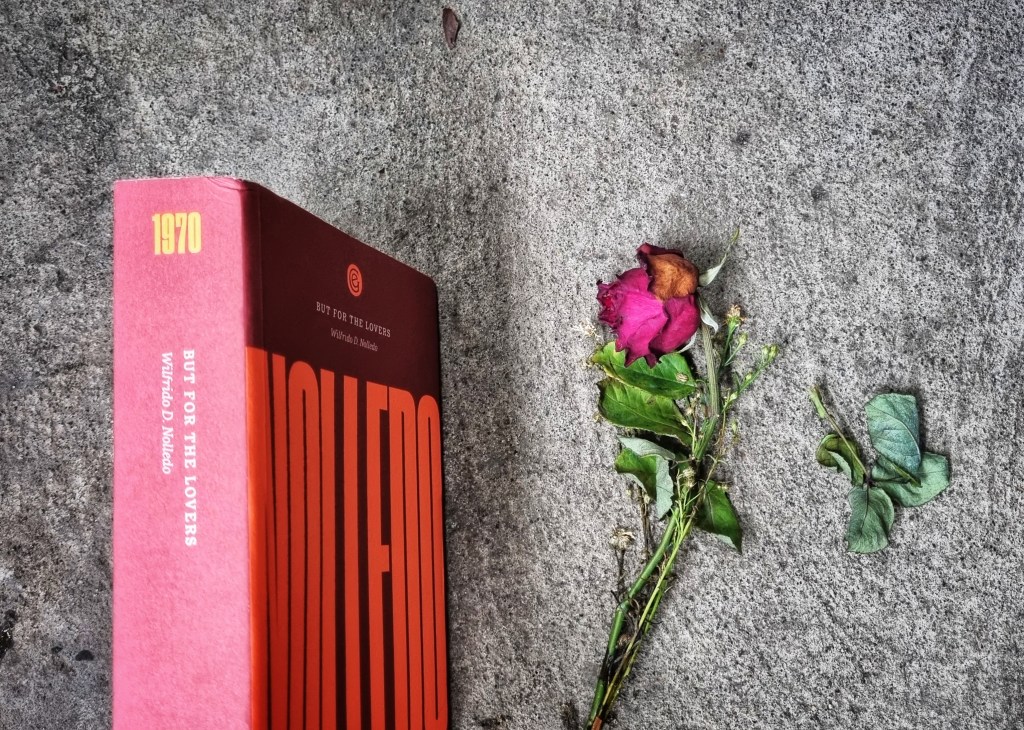

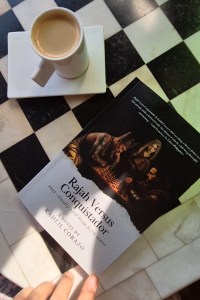

Speaking of Home… I have never read a novel that came this close to home! As a descendant of a binukot, this book felt so personal and empowering to me. The soul of the binukot does not play second fiddle to anything in this novel.

By reading Rajah Versus Conquistador, I seem to have circumnavigated July and circled back to Cebu. The title refers to Magellan as the Conquistador, and Humabon as the Rajah.

Humabon, in Zweig’s words, “was no such unsophisticated child of nature… He had already eaten of the tree of knowledge, knew about money and money’s worth… a political economist who practiced the highly civilized art of exacting transit dues from every ship that cast anchor in his port. A keen man of business, he was not impressed by the thunder of the artillery or flattered by the honeyed words of the interpreter… he had no wish to forbid an entrance to his harbor. The white strangers were welcome, and he would be glad to trade with them. But every ship must pay harbor dues.”

Often cast as a traitor or as someone who’ll always be lesser than Lapu-Lapu in Filipino eyes, Corazo’s Humabon agrees with Zweig’s Humabon: a cosmopolitan ruler who defies simplification. There is much to be said about this work; from the witty language where Bisaya humor often raises its head, to rethinking our past and the deeper meaning to our myths, to the skillful crafting of the key players. Corazo does not merely reconstruct complex characters from the past, he gives readers a perspective of history “viewed not from the deck of a Spanish galleon but from behind the woven walls of a payag…”

And who lives behind these amakan walls? The women. This is what makes Corazo’s work especially meaningful to me. He brings the hidden women to light and by doing so, honors those who never made it to official records but who nonetheless steered the course of history through their quiet power, and who continue to do so.

“Each generation of binukot learns to reshape herself.”

To which Ruby Ibarra gives a brilliant answer: “Ako ang bakunawa.”

These were last month’s books and soundtrack.