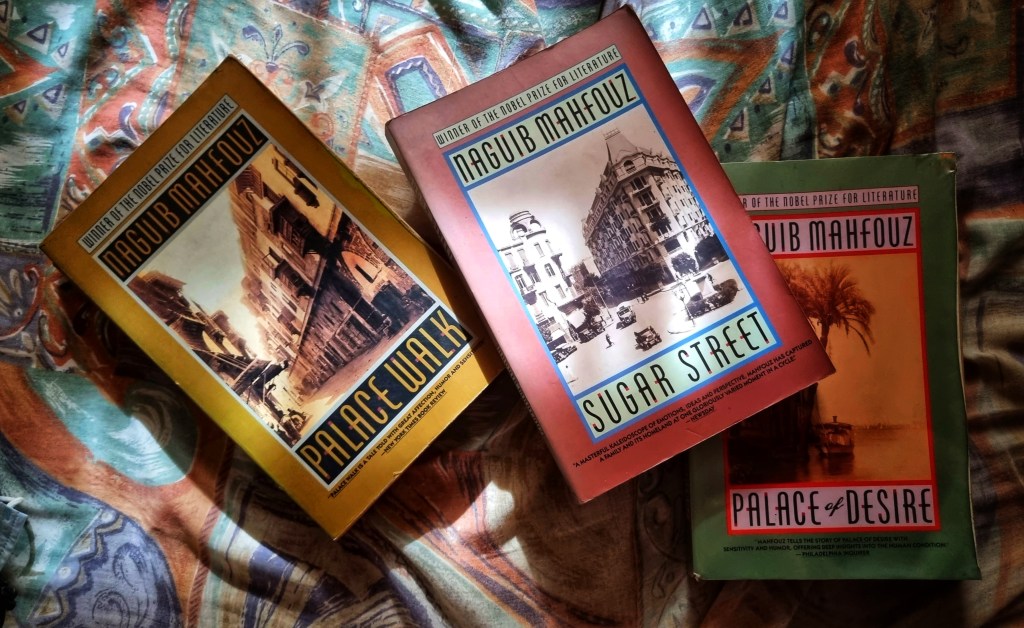

There are better editions with attractive new covers now. Mine still carry the designs of the first American edition of the English translation, but I love how the first volume depicts the antique mashrabiyas of Old Cairo. These projecting windows with intricate latticework are some of my favorite features of traditional Islamic architecture. They seem to me exemplars of how a thing of beauty and tradition can become a refuge or a prison.

And yet, not even these mashrabiyas could shield Ahmad Abd al-Jawad and his family from life, love, death, and a changing world.

It is often said that the Cairo Trilogy is a family saga spanning three generations, from the period of the Egyptian revolt against British colonizers in 1919 to the final days of the Second World War. But it is more than a family saga: It is an astute record of a society, a city, a nation, and a world in transition.

I admit that I found good reason to put the first volume down. I was constantly infuriated by how women were perceived and treated by the male characters, by how men justified their immorality and hypocrisy and got off scot-free while women were punished severely for the most innocent blunders, and by how women themselves accepted this as the natural order of things. Those passages were deeply frustrating.

But Mahfouz’s exquisite storytelling carried me through. He does not so much describe Cairo as transport me there — into the volatile political scene of an Egypt yearning for independence, through its wondrous or disreputable backstreets and alleys, and especially into the women’s cloistered lives so I could hear the questions brewing in their hearts, and eventually to the reflection of society’s gradual development through the change in attitude toward women and their education.

In this trilogy, imperial tyranny juxtaposes with tyranny in the family, but through it all, an incredible compassion and empathy emanates from Mahfouz who humanizes everyone, even the tyrants.

Before I knew it I was at the final page of the last volume, not quite ready to let go, and contemplating on the fact that I had just read one of the finest works of literature ever written.