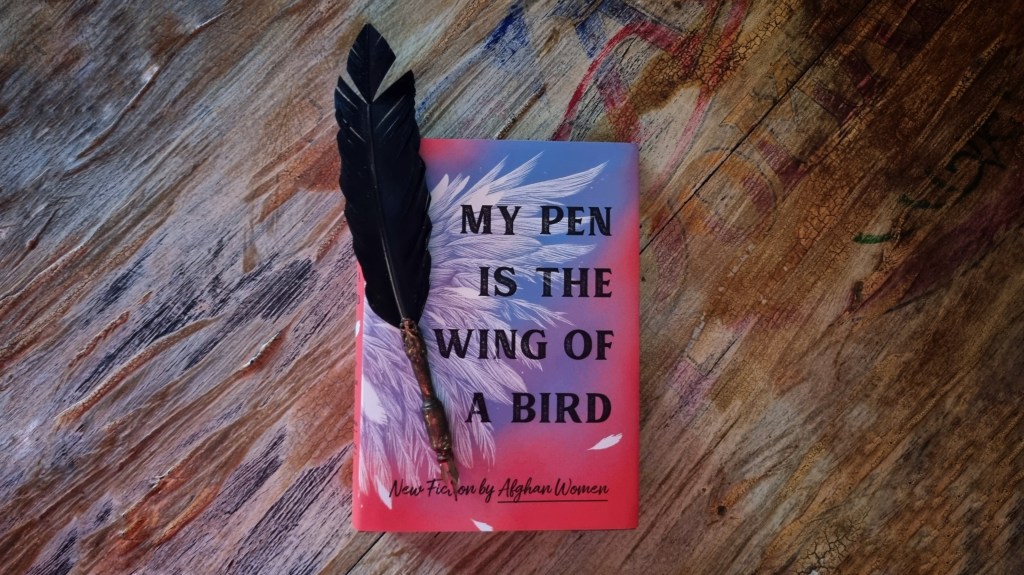

This book came into my possession on International Women’s Day. That day I was asked to speak at an event in celebration of Woman; and as one who never goes out without a book (in case of emergency), I slipped this in my bag on the way out. I was early at the venue so I took this out and flipped the title page. It read:

“My pen is the wing of a bird; it will tell you those thoughts we are not allowed to think, those dreams we are not allowed to dream.”

Batool Haidari, Untold Author, International Women’s Day 2021

The line was written on exactly the same day three years earlier. That’s when I knew I brought the right book with me.

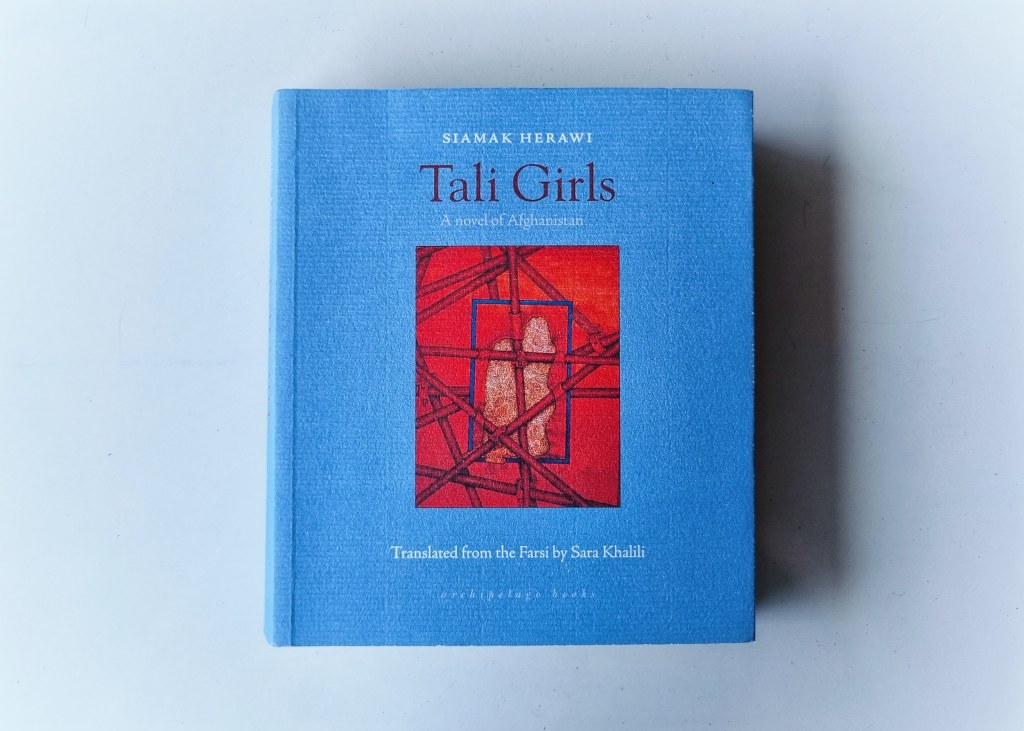

The first open call inviting Afghan women to submit short fiction came in 2019. The creation of this anthology and the translation of the pieces from Afghanistan’s two principal languages, Dari and Pashto, pressed on through more than just power outages and internet service interruptions, but also a global pandemic lockdown and the Taliban takeover in 2021. The book that now sits on my shelf is a triumph.

As anyone might have guessed, there is little happiness here. But it makes us see that there is humanity, kindness, and so much more to Afghanistan’s stories than just war. As in any short story collection, some stories have more literary merit than others, but every single one deserves our attention if we wish to educate ourselves and see a more thorough picture of Afghanistan and the world we live in — especially when their humanitarian crisis continues even as the world’s attention is no longer on them.

“My pen is the wing of a bird; it will tell you those thoughts we are not allowed to think, those dreams we are not allowed to dream.”

This line made me realize the wide gulf between literature by women from places of conflict and the first world. In literature from the first world, this would refer to careless and obsessive romantic affairs, and the women who write about these things are lauded for their rawness and honesty. In literature from marginalized communities, the thoughts they are not allowed to think and the dreams they are not allowed to dream are education, work, the freedom to do the right thing, and the freedom to live. A dose of the latter is always a healthy reality check on the disparity present even within women’s literature.