“Today the West often views Islam as a civilization very different from and indeed innately hostile to Christianity. Only when you travel in Christianity’s Eastern homelands do you realize how closely the two religions are really linked. For the former grew directly out of the latter and still, to this day, embodies many aspects and practices of the early Christian world now lost in Christianity’s modern incarnation… Certainly if John Moschos were to come back today it is likely that he would find much more that was familiar in the practices of a modern Muslim Sufi than he would with those of, say, a contemporary American Evangelical. Yet this simple truth has been lost by our tendency to think of Christianity as a Western religion rather than the Oriental faith it actually is. Moreover the modern demonization of Islam in the West, and the recent growth of Muslim fundamentalism (itself in many ways a reaction to the West’s repeated humiliation of the muslim world), have led to an atmosphere where few are aware of, or indeed wish to be aware of, the profound kinship of Christianity and Islam.” — William Dalrymple, From the Holy Mountain

Hagia Sophia, followed by mosaics, lots of them: These are the things that initially come to mind whenever I encounter the word “Byzantine,” and I suspect I am not alone in this. And because it is art that outlives the rise and fall of empires, there is almost nothing else we can clearly visualize about Byzantine beyond its art, architecture, and its leading players in history.

“The sacred and aristocratic nature of Byzantine art means that we have very little idea of what the early Byzantine peasant or shopkeeper looked like; we have even less idea of what he thought, what he longed for, what he loved or what he hated,” writes William Dalrymple.

But once upon a time, circa 580 AD, a monk called John Moschos traveled with Sophronius the Sophist across the empire including the three greatest Byzantine metropolises — Constantinople, Antioch, Alexandria — and wrote about it. In a book called Spiritual Meadow, Moschos detailed what he saw, whom he met, the heresies he witnessed, and stories about common folk, “the sort who normally slip through the net cast by the historian.”

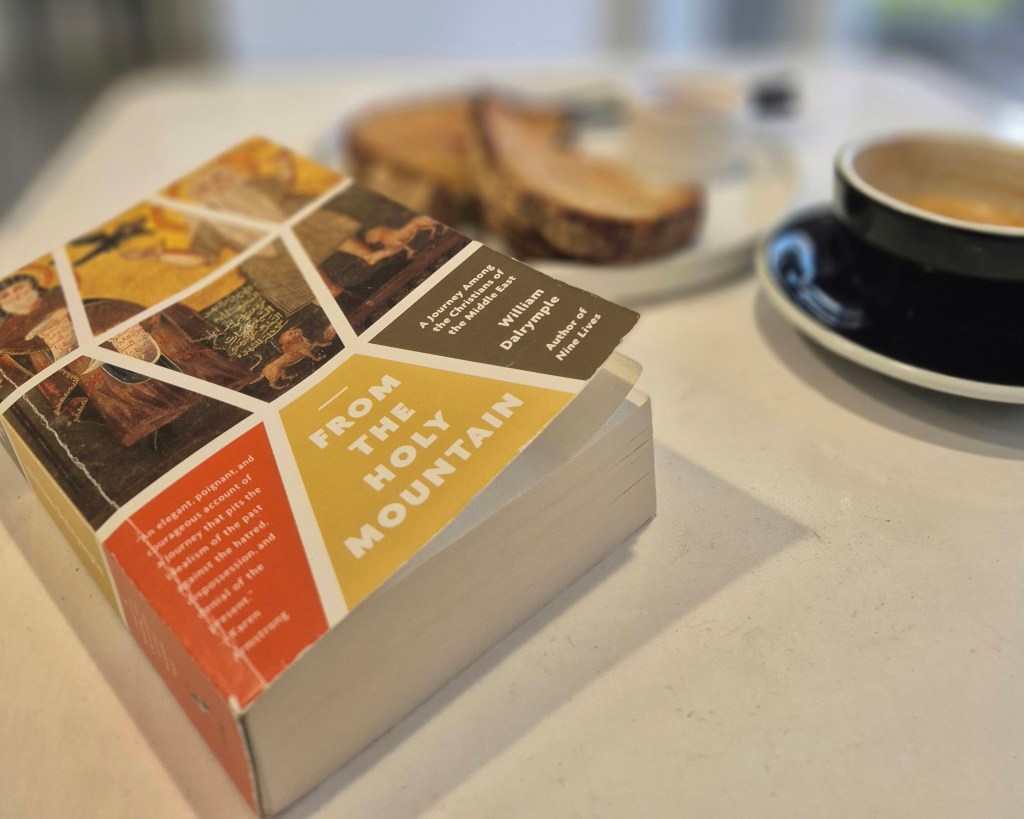

It was this book that Dalrymple used as a guide to travel through the eastern Mediterranean world in 1994, a world that is now predominantly Islamic, but a world that once was predominantly Christian (not in deed, of course, but by religious affiliation) for hundreds of years, from the age of Constantine to the dawn of Islam in the 7th century.

This journey among the dwindling population of Eastern Christians begins in the Monastery of Iviron in Mount Athos, an autonomous region in Greece that is under the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople. To this day, women are prohibited from entering the monastic community. It is, therefore, a place I cannot travel to even if I wanted to.

And this is the service Dalrymple does for his readers: To visit places inaccessible to us, to experience cultures and traditions unheard of and never to be seen again, “to do what no future generation of travelers would be able to do: to see wherever possible what Moschos and Sophronius had seen, to sleep in the same monasteries, to pray under the same frescoes and mosaics, to discover what was left, and to witness what was in effect the last ebbing twilight of Byzantium,” and then tell the tale. (A sad validation of this slightly conceited claim is the wistful realization that most of the Syrian Byzantine sites mentioned in this book became casualties of war several years after its publication.)

The stunning architecture that William Dalrymple describes with an eye for detail and a penchant for lyricism; the coming across of endangered languages such as Turoyo, the modern Aramaic spoken in the Tur Abdin region in southeastern Turkey and northern Syria, “where Jesus could expect to be understood if he came back tomorrow”; the discovery of a musical mystery, an ancient form of plainsong in Syria that could possibly be the direct antecedent of the Gregorian chant; the Eastern roots of Celtic illuminating art and how the trajectory of Renaissance art owes it to John of Damascus, an Arab Christian monk; the author’s observation that “Muslims appear to have derived their techniques of worship from existing Christian practice” and that “Islam and the Eastern Christians have retained the original early convention; it is the Western Christians who have broken with sacred tradition”; perspectives on the Armenian genocide, the Kurdish conflict, the Lebanese Civil War, and the Israeli–Palestinian situation at the time; the realization that Byzantine Palestine was dominated by Christians and for eight hundred years the Jewish community was a minority; accounts of Muslims praying in Eastern churches, “the Eastern Christians and the Muslims have lived side by side for nearly one and a half millennia, and have been able to do so due to a degree of mutual tolerance and shared customs unimaginable in the solidly Christian West”; and most remarkably, the awareness that, oftentimes, people are not as hostile and as divided as governments and ideologies want us to believe; these are a few of the things that will have readers brimming by the time they get to the last page.

This is essential Dalrymple right here — a book that will leave one richer for having read it.

Thank you, dear Anna, for this most wonderful recommendation! 🤍

I am glad you enjoyed this gem of a book. Looking back, I think it might have been this book that really sparked my interest in Byzantium and this region of the world . X

LikeLiked by 1 person