Aswan. This is where Egypt begins. It only seemed logical to begin my excursions to the ancient Egyptian archaeological sites here.

In one of Aswan’s stone quarries, one site has intrigued me almost as much as the pyramids. Had it been completed, it would have been the largest obelisk ever built by the ancient Egyptians. The speculation that it had been commissioned by Queen Hapshetsut added to my wonder. Needless to say, within an hour after landing in Aswan, I was already at the site of the Unfinished Obelisk, fascinated by the existing evidence of the ancients’ construction process.

The following day, I set out early and hired a private car to take me to Abu Simbel. The ride itself was exciting as I witnessed a most enigmatic sunrise, passed checkpoints due to the proximity to the Sudanese border, saw more Nubian villages and the place where they quarantine camels from Sudan, drove through an otherworldly terrain, and finally beheld the twin temples originally carved out of the mountainside in the 13th century BCE, during the reign of Ramesses II.

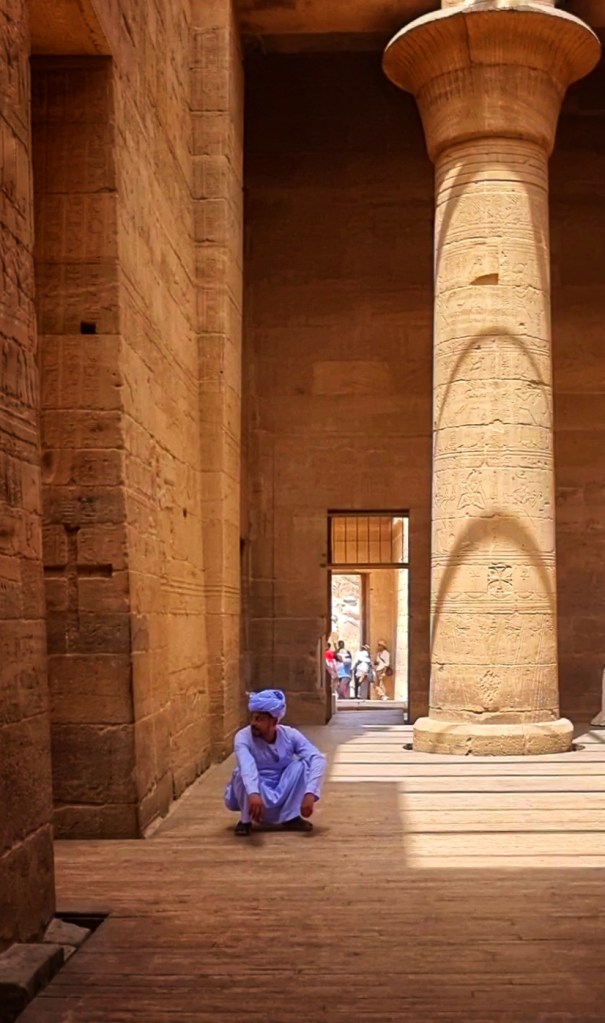

But when it comes to idyll, Philae Temple Complex takes the throne. A small ferry took me to an island on the Nile and I was immediately transported to the pages of Mahfouz’s Rhadopis of Nubia. The Temple of Isis built in the reign of Nectanebo I in 380-362 BCE is the island’s most striking feature, and yet through the different architectural structures, one could see the Pharaonic, the Ptolemaic, the Romans, and the Christians, stamping their identities on the landscape. It has never been this clear to me; how architecture IS identity.