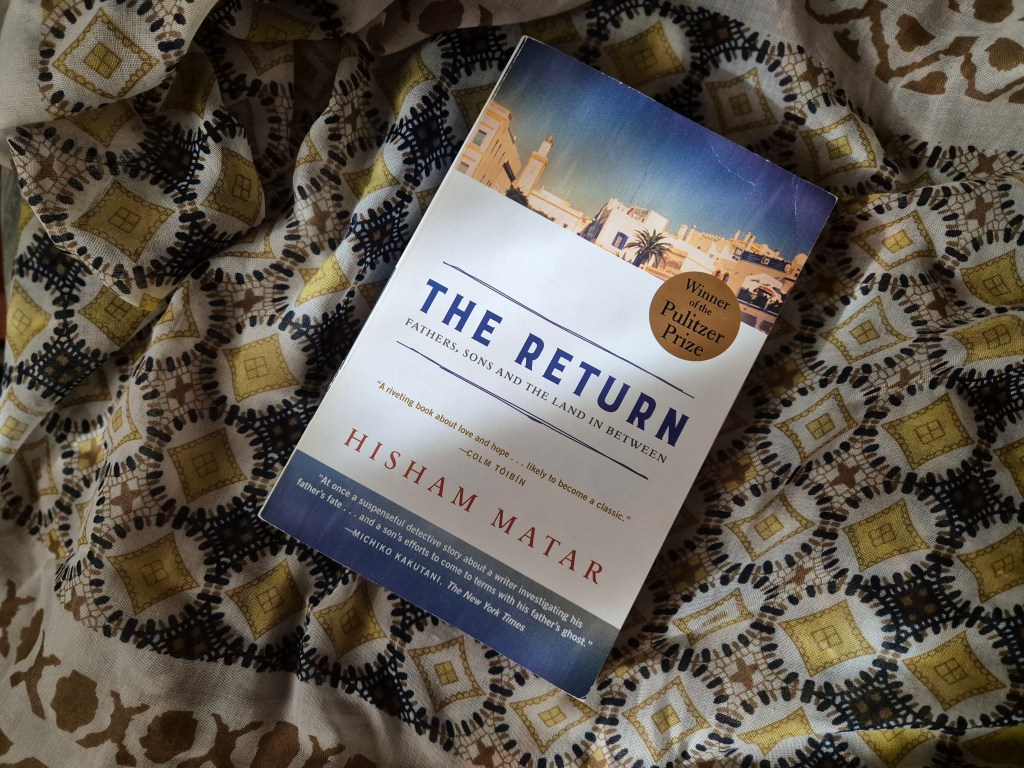

Part of this month’s reading agenda was to read Hisham Matar’s earlier books — which have been left untouched on my shelf for years — in preparation for his latest novel that made it to this year’s Booker Prize longlist. His debut novel, In the Country of Men, did not exceed my expectations, but after having just read The Return, and reeling from the force and the beauty of this work, I am hesitant to read anything else by him for the time being. This, right here, could be peak Hisham Matar.

I was in my late twenties when news of Qaddafi’s assassination hit the headlines, but even after that, and apart from a vague idea that it had been under Roman dominion in older times and under a dictatorship in recent times, I remained ignorant of Libya’s modern history.

“All the books on the modern history of the country could fit neatly on a couple of shelves. The best amongst them is slim enough to slide into my coat pocket and be read in a day or two,” writes Matar in The Return. “Libya has perfected the dark art of devaluing books.”

The Qaddafi censorships were culpable for the dearth of Libyan literature, and it comes as no surprise that our generation reads so little of Libya beyond occasional one-liner news tickers.

Matar changes that for his readers and lights up the void. The book is a formidable testament to a bleeding country and of the atrocities of Muammar Qaddafi’s regime and its complex aftermath, and it is also a moving account of the invisible and invincible bonds that tie fathers and sons.

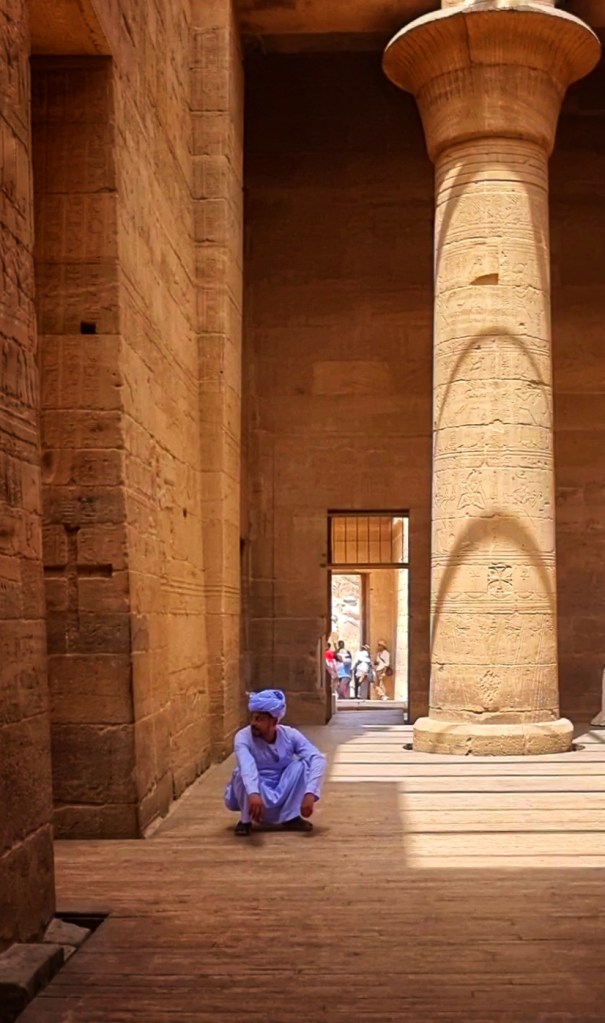

The story of a son returning to Libya seeking answers to his father’s disappearance is poignant enough, but Matar writes beyond the journalistic and allows his background in art and architecture to seep into his prose. This adds a poetic aspect to an attention to detail that makes the writing engaging and lyrical.

For this book to have won the 2017 Pulitzer Prize for Biography/Autobiography and to have made it to NYT’s 100 Best Books of the 21st Century was, I suppose, inevitable.