February 11, 2021

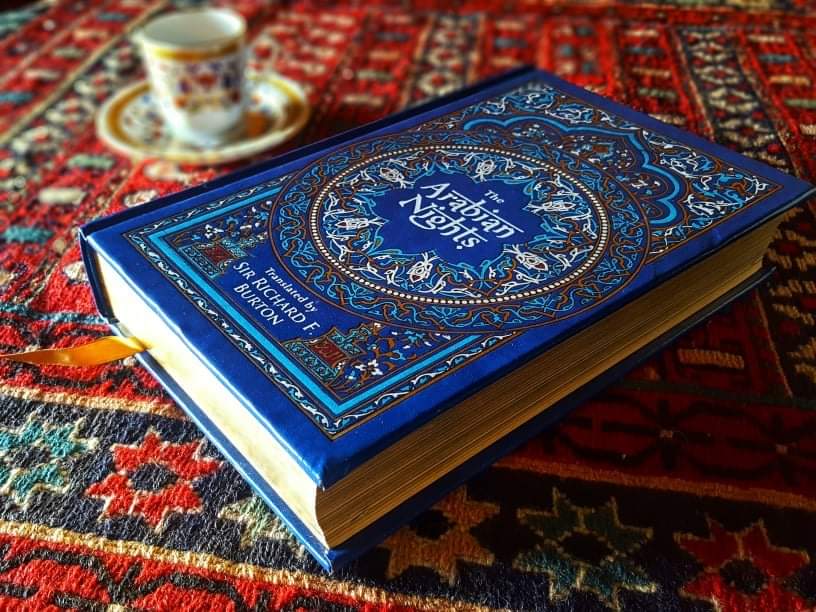

For this reading venture, I chose the controversial translation by Sir Richard Burton (1821-1890). I had to wade through hundreds of pages of old-fashioned language, terminology that are deemed politically incorrect nowadays, some unusual words that Burton coined himself, and content that was considered pornography in Burton’s time. (On a side note, Burton also translated the Kama Sutra and its Tunisian counterpart, The Perfumed Garden. Given those inclinations, this was not one of the watered-down versions we used to find lying around our grandparents’ living rooms.)

This edition has fine and tastefully-colored illustrations that are oases from the antiquated writing style that 21st Century eyes are no longer accustomed to. A collection of Eastern folk tales and stories compiled during the Islamic Golden Age, I enjoyed coming across real historical figures from that era that were woven alongside the fictional characters.

Haroun al-Rashid, the fifth Abbasid Caliph who ruled from 786-809 appears in many of the stories along with his Persian vizier Jafar who, by the way, was not a villain. The Islamic Empire was said to be at its most powerful under this caliph’s reign. They traded and maintained diplomatic ties with China, and because stories were also traded along the Silk Roads, it may not be too surprising that in the Arabian Nights, Aladdin is actually Chinese.

On the year Al-Rashid became caliph, his son Al-Mamun was born, and it would be Al-Mamun’s obsession for knowledge and a large-scale commissioning of translations of ancient texts from Mesopotamia, Persia, Greece, and India that would result into the Translation Movement — and perhaps, in addition, this compilation.

As one who finds this region of the world and that period of history intriguing, I still find this worthy of any book-lover’s shelf space. However, I now understand why later writers feel compelled to refashion the stories into something more relatable, or make adaptations for younger audiences without the sexual imagery, or modify the individual stories with a more discernible moral aim.

But whether we like it or not, the Arabian Nights in its entirety has revolutionized and influenced storytelling for centuries. After having read it myself, I realized that there is an aspect that is not emphasized enough: Hers was an unselfish act. Scheherazade volunteered herself at the risk of death to prove King Sharyar’s stereotypes wrong. By so doing, she saved not only her life, but other women’s lives as well — and through an unlikely medium!

After all, isn’t there inside each of us a Scheherazade, a being who depends on the magic of stories to survive?